Mike Lloyd, Victoria University of Wellington (mike.lloyd@vuw.ac.nz)

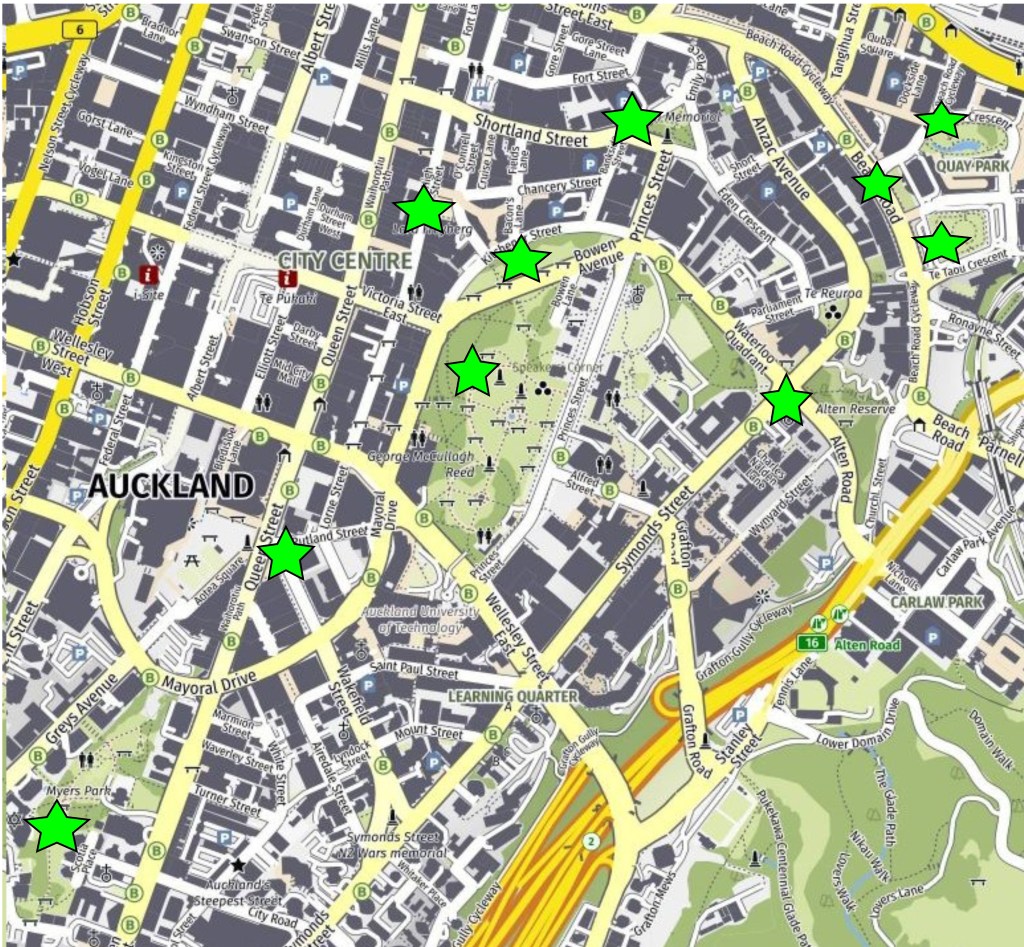

In his work on war memorials in New Zealand, Jock Philips calls Whanganui ‘the war memorial capital of the world’.[1] Clearly, the expression is used for rhetorical effect, not really being open to empirical evaluation. Nonetheless, in the example of Whanganui’s small riverside reserve originally known by Māori as Pākaitore, then in 1900 to become Moutoa Gardens, but then in 2001 to return to being called Pākaitore,[2] substance is found for Philips’ expression. The less than one hectare site contains three significant war memorials. As Philips details, ‘The Maori name was Pakaitore, the place (pa) where food (kai) was given out (tore)’, pointing to the strong significance to Māori of this gathering place. The renaming as ‘Moutoa Gardens’ overrode this initial sense, emphasising the 1864 Battle of Moutoa with its complex array of antagonists.[3] Eventually, related to the 1995 occupation of Moutoa Gardens, the land was vested in the Crown, with the return to the name Pākaitore. The presence of the three war memorials on the site is testament to this complex history, which can still invoke strong emotions. An unintended consequence of the well documented nature of these events is help in telling an untold history: the story of the planting and removal of palms in Pākaitore. This has gone on for well over 120 years, as we can see by considering the 1920 photo shown in Figure 1.

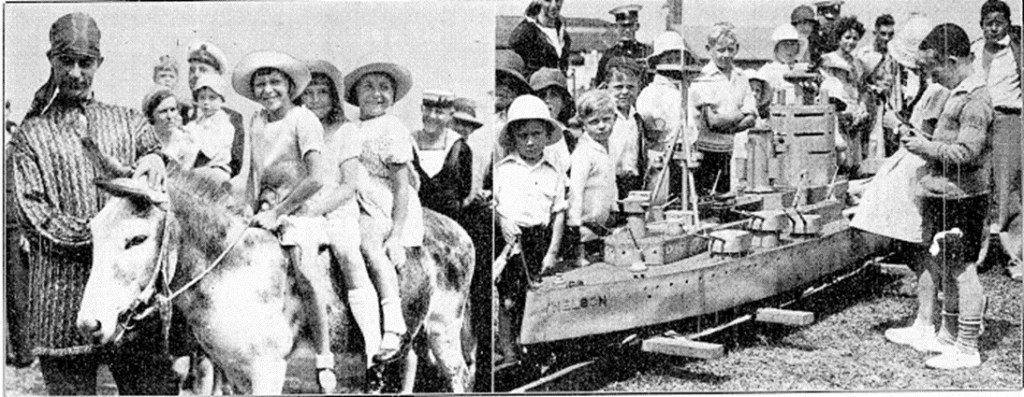

Close scrutiny of Figure 1 shows one of the two earliest palms to be planted in Pākaitore. Magnification of the photo shows that past the flagpole is a palm able to be identified (from subsequent information) as a Washingtonia robusta (common name Mexican fan or skyduster palm). There is no record of the palm’s planting. However, in 1911 Whanganui newspapers carry reports of ‘choice varieties of palms’ being planted on Durie Hill, and very old W. robusta can still be seen there. The reports note that these palms were imported from Australia,[4] and it seems fair to assume that the sole specimen in Pākaitore came from the same shipment, meaning that a planting date of circa 1911 looks reasonable. At this time Mexican fan palms were being planted in other cities, for example Auckland and Napier, along with other introduced palms. But in Pākaitore we can see palms not commonly found in early New Zealand palm landscaping. Figure 2 shows this trend began with the early planting of a nikau palm (Rhopalostylis sapida).[5]

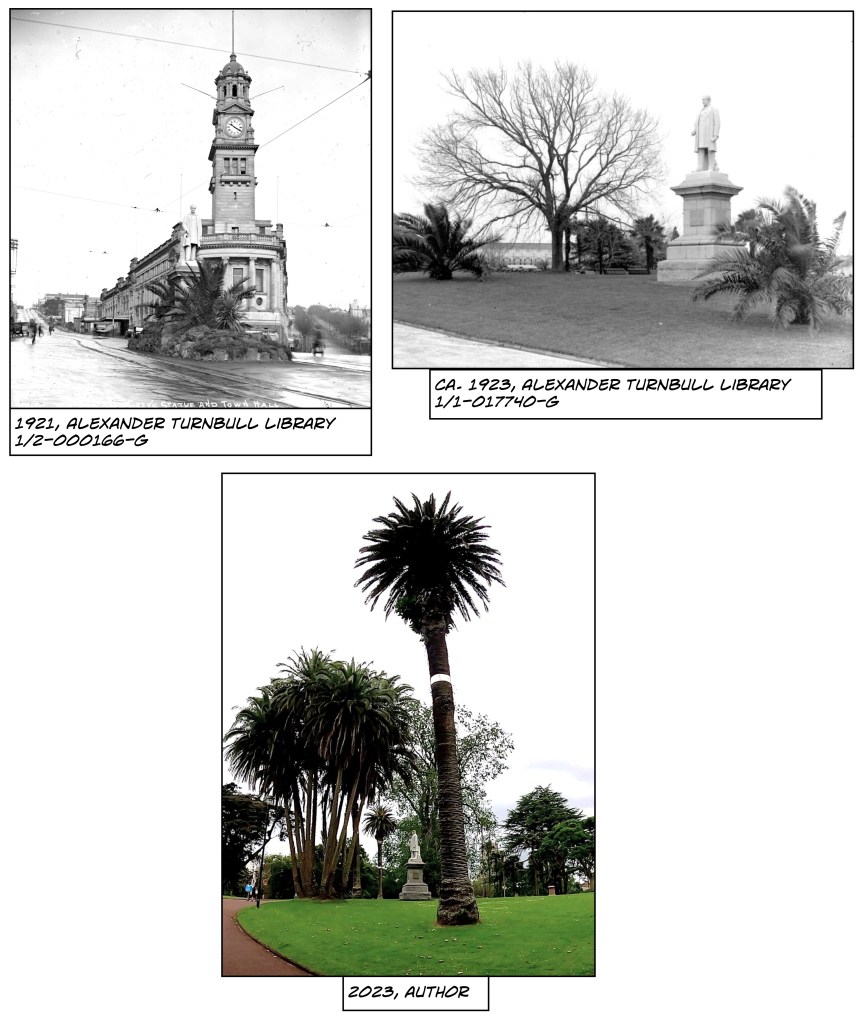

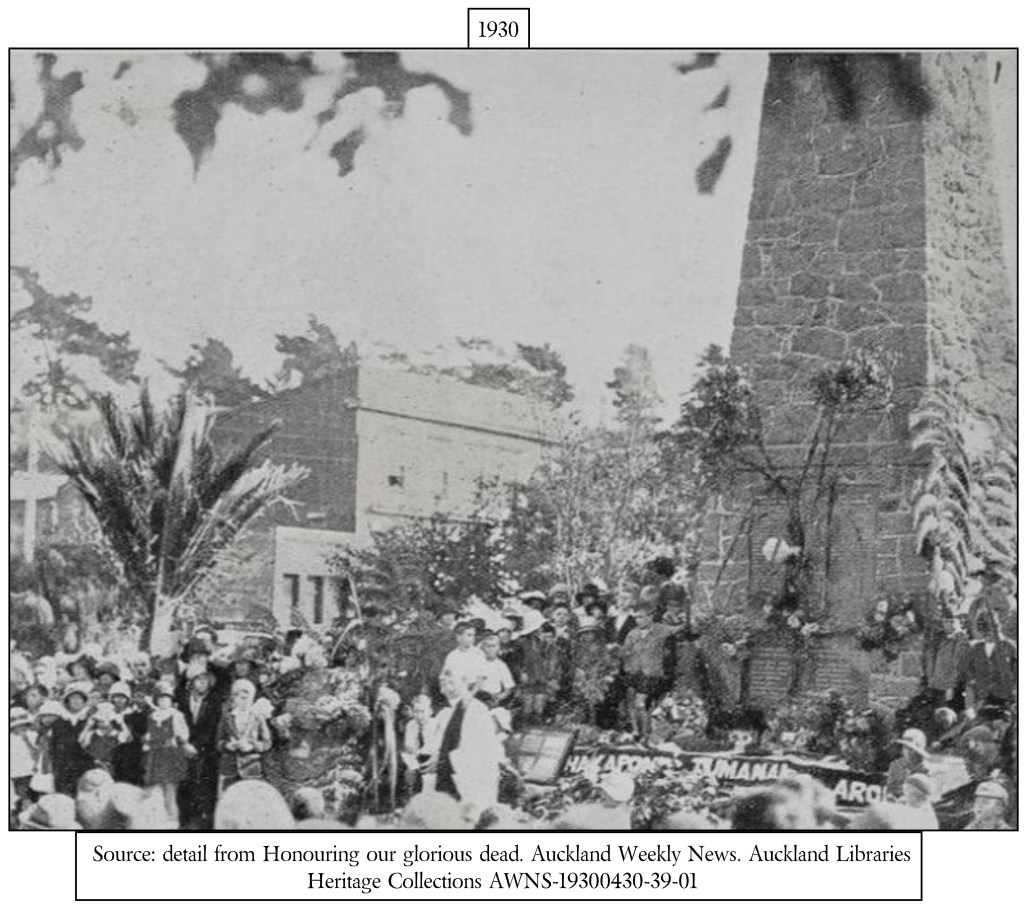

The photo is a detail from an Auckland Weekly News collage of 7 photos taken during Anzac Day observances on April 30, 1930. The cenotaph in view to the right is the Māori World War One Memorial built in Pākaitore from 1924 and unveiled on Anzac Day 1925.[6] We see a good crowd gathered for the ceremony, and there to the left of the memorial is a nikau palm. The height of the visible leaf node suggests the palm has a developed trunk, which can sometimes take over 10 years to start appearing.[7] This and its height suggest the palm is about 20 years old. Therefore, it possibly could have been planted before, or at least within a few years of, the Mexican fan palm’s planting. There is no available record or photo that can verify this date. However, there is other contextual information that partly helps in answering this question. In 1912 in a report on ‘Local and General’ news it is reported that ‘Mr Gregor McGregor has sent another large shipment of plants to the borough nurseries, including about twenty well-grown nikau palms.’[8] Gregor was born in Matarawa Valley to the south-east of Wanganui, worked in the upper reaches of the Whanganui river, spoke te reo, and was a noted promoter of native flora for planting in the Whanganui region.[9] Moreover he was married to Pura McGregor (née Te Pura Manihera), whose father was killed in the Battle of Moutoa, and whose uncle was Major Kemp (Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui), memorialised in the Kemp monument built in Pākaitore in 1911[10]. Both McGregors were involved in the Wanganui Beautifying Society, particularly with the development of the Rotokawau Virginia Lake Reserve, where a memorial still stands to commemorate Pura McGregor.

It is not able to be confirmed, but it does look highly likely that the single nikau planted in Pākaitore came from the donation of nikaus, sourced by Gregor McGregor either in the Matarawa Valley farm or from bush remnants in the upper Whanganui River. An item on ‘Town Talk’ in 1931 notes that ‘A Nikau in Moutoa Gardens which has burst into flower has been a subject of interest to many people during the past few days.’[11] This aligns with the description of ‘well-grown’ nikaus sent by Gregor McGregor to the council, as it is stem size rather than age that is a better indicator of first flowering in nikau.[12]

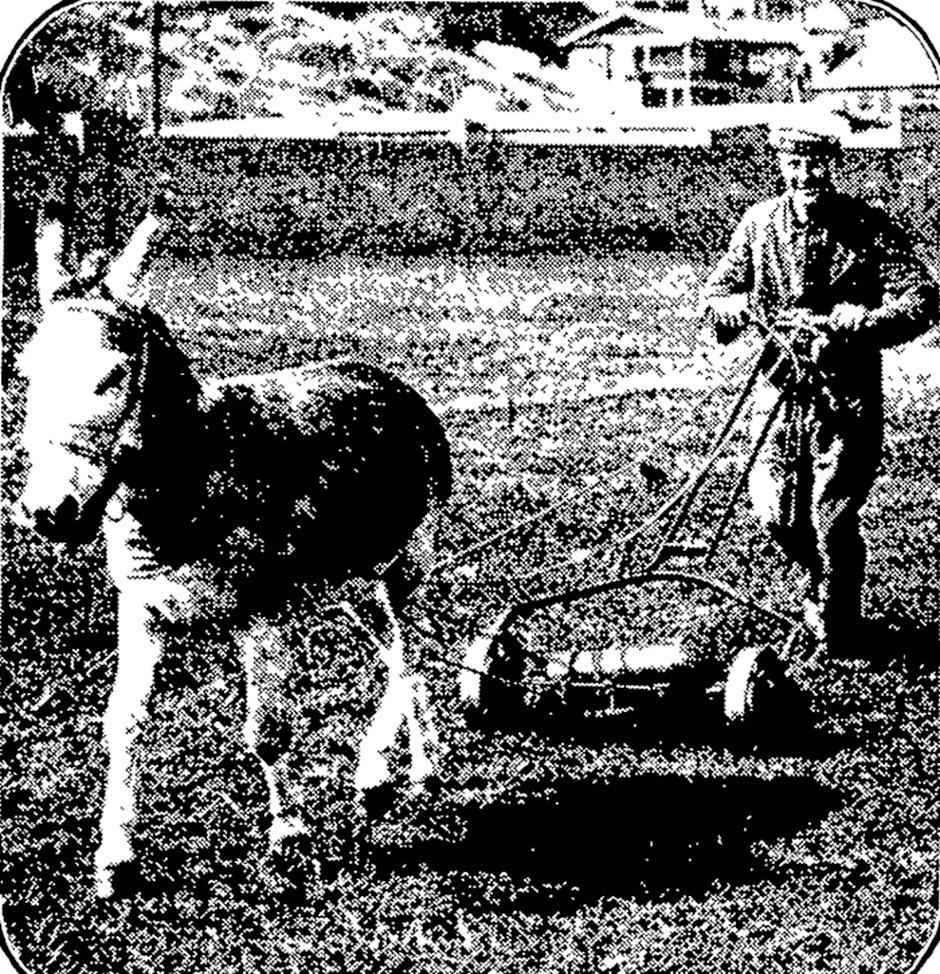

Unfortunately, there are no available photographs that show a younger nikau in Pākaitore, nor any mention in newspapers of its planting date. In some way trying to ascertain a planting date is a moot point, as there is no doubt about its later fate: it was removed (or perhaps died). The mystery is when this happened and why. Requests to the local council and museum archivists found no information on these matters. However, there is some photographic evidence establishing that the nikau was present into the early 1960s, and interestingly this also shows two other palms in Pākaitore. Figure 3 is one of the very few photos that shows both the nikau and the two newcomers.

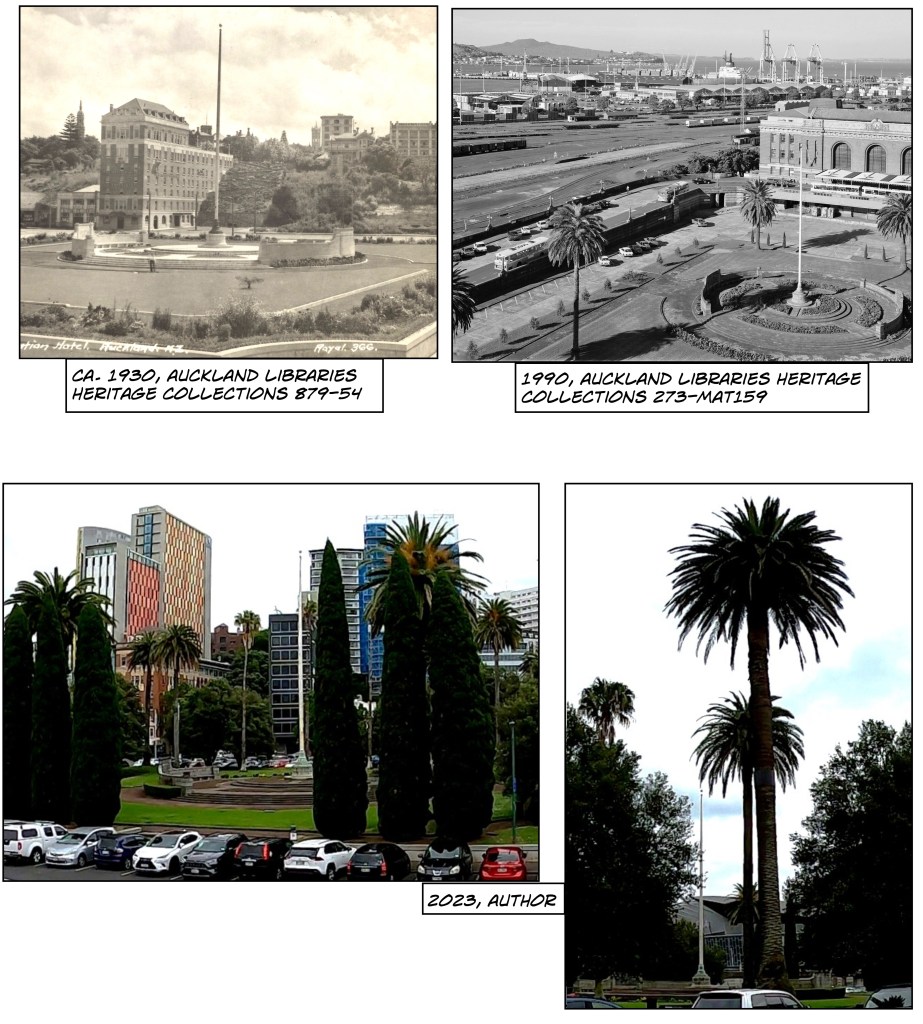

Obviously, the two newcomers are Phoenix palms. Their planting was noted in the Wanganui Chronicle as follows: ‘Phoenix canarianthus [sic] was planted in Moutoa Gardens yesterday. These plants, which come from the Canary Islands, were grown from seeds in the municipal nursery. A number have already been planted around the Art Gallery and at Virginia Lake and are in a flourishing state’.[13] The photo shows the 34 year old Phoenix palms having the robust stature we would expect at this age. The planting as a pair in front of a building – the Whanganui courthouse – was a common landscape trope at the time. The nikau is obviously a smaller palm in terms of crown spread and trunk diameter, but we can see it is not an insignificant specimen, and has set seed. Clearly, the photo also shows that the other trees in Pākaitore are gaining in stature, with a red flowering Eucalytpus (renamed Corymbia), a pohutakawa, and an English oak all visible. Whereas the fate of the nikau after this is a mystery, there is no similar mystery as to the fate of the two Phoenix palms. Figure 4 indicates this.

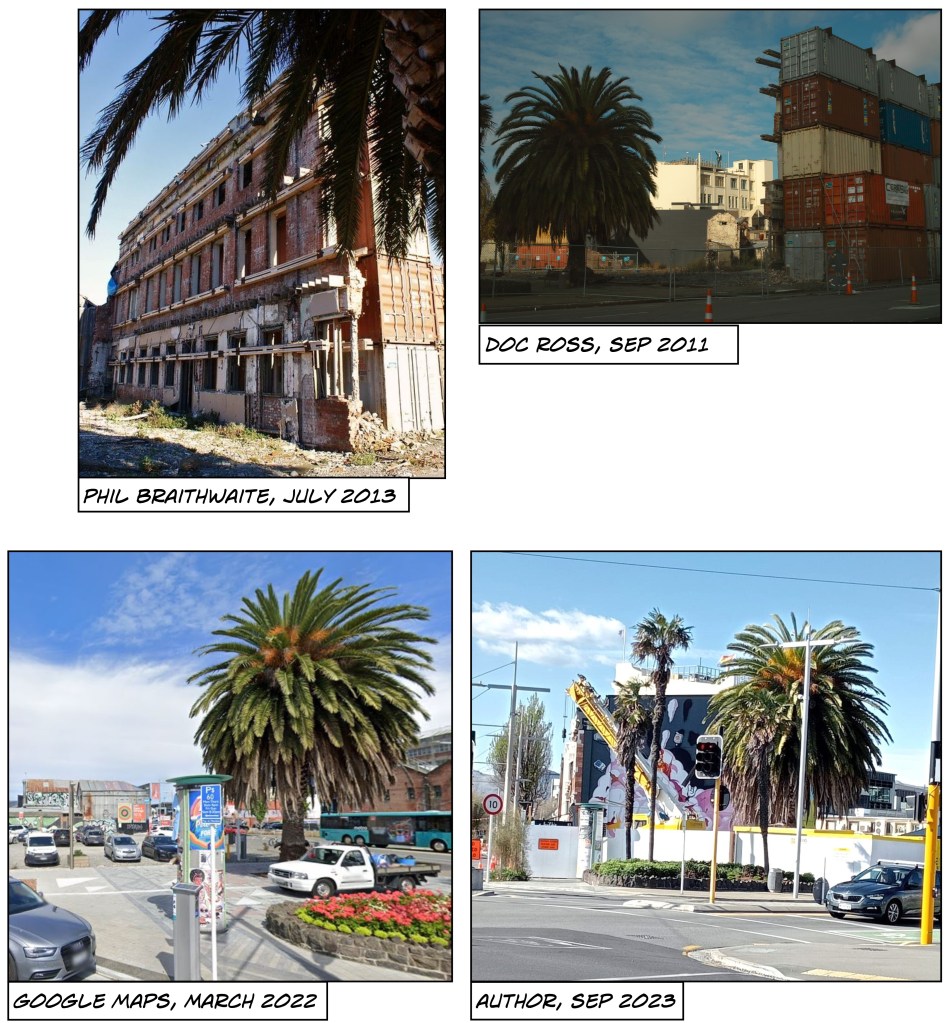

The top photo shows the early stages of the construction of a new Whanganui courthouse building. Other aerial images show that with the removal of the old wooden courthouse the two Phoenix palms were left in-situ, but by March 1966 the one to the right was removed. The new courthouse was larger and also differently angled into Pākaitore, thus necessitating the removal of the southern-most Phoenix palm. It is another small mystery as to why the northern-most Phoenix palm, initially left untouched, was removed by 1967 as indicated in the LINZ Retrolens photo. At this time there were certainly good numbers of Phoenix palms in Whanganui, many of which were later included in the Register of Notable Trees, so perhaps the loss of these two in Pākaitore was not seen as an issue. Additionally, it does not seem the case that this removal is an early case of a developing preference for native flora. The removal, probably shortly after 1962,[14] of the nikau palm indicates this, as do the later developments indicated in Figure 5.

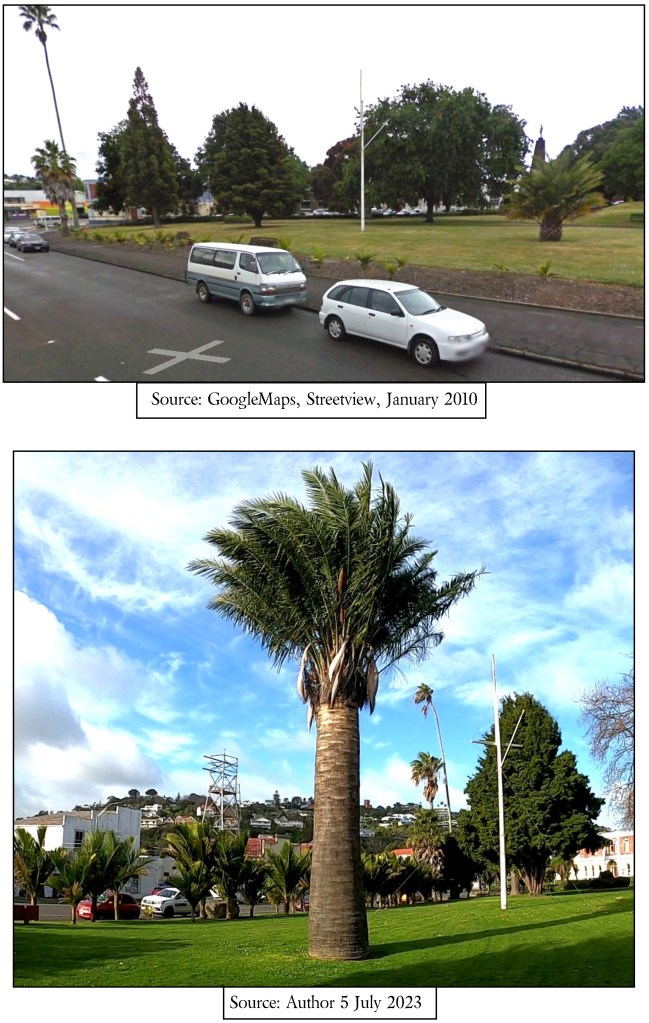

The figure shows several interesting developments in Pākaitore. The 2010 GoogleMaps streetview photo shows to the centre right a young Jubaea chilensis (common name Chilean wine palm). Secondly, we can see that two new W. robusta now grow next to the by now very tall early planted palm (here it is approximately 100 years old). The fact that the single specimen was complemented by two others is not unexpected, as the tallness of the palm coupled with its relatively slim trunk makes a single specimen seem a bit ‘leggy’, hence it is more commonly planted in groups. The 2010 Google streetview also shows in the foreground a new mass planting of nikau (totalling over 50), actually extending right along the side of Pākaitore that faces the river. The 2023 photo shows that despite claims that Chilean wine palms are slow growing, the sole specimen on view here has made strong growth, clearly showing the typically massive trunk they are known for.[15] Interestingly, available photographic evidence suggests the palm was not planted until after 1995.[16] It is in excellent health, as are the nikau which have also made good growth in the 13 years between the dates of the two photos, something reiterated in Figure 6.

The final figure clearly indicates that in the future the nikau palm set is going to be a significant arboreal feature of Pākaitore. Of course, they are relatively slow growing, but there is no doubt that with time the mass planting will constitute a significant version of vernacular palm landscaping in New Zealand. It will more that make up for the removal of the early nikau. But the photo also shows that the nikau are not the only arboreal elements that will become more striking as they age and grow. The large tree to the top right of the photo is a kauri, in excellent health. The trio of W. robusta are likely as a collective to be more impressive looking than the previous sole specimen. And presumably, even though of course it is an exotic, the Chilean wine palm will remain and look even more impressive with age. The mystery of the initial removal of the early-planted nikau remains, as does the part-mystery of the removal of one of the Phoenix palms, but the current progressive state of Pākaitore means a search for the explanation of both removals is relatively unimportant.[17] An eye to the future, coupled with the accountability associated with better record-keeping, should mean that within Pākaitore palms of all kinds will continue to prosper, along with the other trees found therein.

Acknowledgements

This blog is dedicated to Oliver Stead (1963-2024) who would have appreciated the nikau palms (and the removal of the Phoenix palms). Thanks to Simon Bloor of Whanganui District Council, and Sandi Black, Whanganui Regional Museum, for help with information. Thanks also to Michael Brown for continued talk about matters arboreal.

Footnotes

[1] J. Phillips, 2006, ‘Wanganui: War memorial capital of the world’, in K. Gentry & G. McLean (eds.), Heartlands: New Zealand Historians Write About Places Where History Happened, Auckland: 72-89.

[2] For details see, Pākaitore Historic Reserve Board, Pākaitore: A History, 2020, H & A Print.

[3] See D. Young, Woven by Water: Histories from the Whanganui River, 1998, Wellington: Huia Publishers.

[4] ‘Local and general’, Wanganui Herald, 12 June 1911, p. 4; ‘Local and general’, Wanganui Herald, 24 August, 1911, p. 4.

[5] Nikau palms were certainly known by early gardeners, including enthusiasts like Clement Wragge and Alfred Ludlam, but in the early 1900s when planting in parks and gardens began in earnest there was a prevalent attitude that they belonged in the bush, and would not thrive in parks and amenity gardens. See, for example, ‘Re Beautifying the streets’, New Zealand Herald, 6 November 1901, p. 7.

[6] E. Morris, Kia Mau ai te Ora, te Pono me te Aroha ki te Ao Katoa: The Māori First World War Memorial at Whanganui’, Turnbull Library Record, 2014, 46: 1-13.

[7] N.J. Enright, ‘Factors affecting reproductive behaviour in the New Zealand nikau palm’, New Zealand Journal of Botany, 1992, 30: 69-90.

[8] ‘Local and general’, Wanganui Herald, 3 October 1912, p. 4.

[9] ‘Our native flora’, Wanganui Herald, 20 July 1912, p. 4.

[10] ‘Pura McGregor, Wikipedia entry, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pura_McGregor; Pākaitore Historic Reserve Board ‘Pākaitore: A History’, p. 25.

[11] ‘Town talk’, Wanganui Chronicle, 5 March 1931, p. 6.

[12] N.J. Enright, ‘Factors affecting…’

[13] ‘Untitled’, Wanganui Chronicle, 1 August 1928, p. 6.

[14] Magnification of the 1967 Retrolens image does not seem to indicate the continued presence of the nikau palm, though it could be in the shadow of other trees. Either way, it is definitely no longer growing as confirmed by a 2023 site visit and consulting Google maps.

[15] Jubaea chilensis is a rare palm in New Zealand. The two largest specimens I know of are planted at George Grey’s Mansion House on Kawau Island, and there is also a large specimen in Monte Cecilia park in Auckland. Interestingly, there is one other specimen in Whanganui – in a private garden in East Whanganui.

[16] A photo in a 1995 article (p. 47) on the occupation of Moutoa Gardens shows no sign of the Chilean wine palm. See C. Brett, ‘Wanganui: Beyond the comfort zone’, North & South, June 1995, 44-59.

[17] It is possible that further information could be found, but given the resources for putting together this short report it is followed no further here. I am open to communication on this matter.