By Shanshan Liu and Xiao Huang, with contributions from Chang Jingyi and Gu Rui

The Zhi Garden Album (《止園圖》) is a set of twenty paintings created in 1627, currently held in two parts by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Asian Art in Berlin. Executed in a delicate and realistic style, the album presents a splendid Ming-dynasty garden from multiple perspectives. The first page is inscribed with the phrase “Panoramic View of Zhi Garden.” Who built Zhi Garden? In which city was it located? When was it constructed? Was the garden depicted in the album a real place, or merely a product of the artist’s imagination? These unresolved mysteries have made The Zhi Garden Album a subject of great interest among international scholars.

In the 1950s, American art historian James Cahill first encountered The Zhi Garden Album in Boston. Attributed to the Ming-dynasty painter Zhang Hong (張宏), the album portrays a grand garden in remarkable detail from various viewpoints. Deeply moved by its distinctive realism, Cahill began a long-term engagement with the work. His later research elevated The Zhi Garden Album as a quintessential example of Chinese realist painting, and he systematically articulated Zhang Hong’s unique place in the history of Chinese art.

In 1978, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York began constructing its Chinese-style garden “The Astor Court” (Ming Xuan, 明軒), James Cahill made a special trip to New York to meet with Professor Chen Congzhou (陳從周), a leading Chinese garden scholar who had traveled to the U.S.A. to provide guidance for the project. Their exchange marked an early attempt at cross-disciplinary collaboration between Chinese garden design and art history. In 1996, Cahill partnered with June Li (李關德霞), curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, to organize the exhibition Paintings of Zhi Garden by Zhang Hong: Revisiting a Seventeenth-Century Chinese Garden. For the first time, all 20 album leaves, previously dispersed across different institutions, were reunited and presented as a complete set.

After returning to China, Chen Congzhou did not forget The Zhi Garden Album. Over several years, he compiled the influential book A Comprehensive Collection of Gardens (Yuan Zong,《園綜》), and included the black and white images of 14 leaves from The Zhi Garden Album, gifted to him by Cahill, as the only visual artwork in the entire volume. Published alongside over 300 garden inscriptions, this marked the first time the album entered the field of Chinese garden scholarship. In 2009, landscape historian Cao Xun (曹汛) discovered a rare surviving copy of Collected Writings from Zhi Garden (Zhi Garden Ji) in the National Library of China. By closely comparing the poems and garden records in the book with visual details from The Zhi Garden Album, he identified the garden owner as Wu Liang (吳亮), the author of the anthology, and successfully located the site of Zhi Garden in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province (江蘇省常州市).

At the invitation of Cao Xun, we established contact with James Cahill and began a collaborative study on Chinese garden painting. In 2012, we co-authored The Immortal Forests and Springs: Garden Paintings in Old China(《不朽的林泉:中國古代園林繪畫》), with the first chapter dedicated to The Zhi Garden Album. As the first scholarly monograph to systematically explore the genre of garden painting in China, Garden Paintings in Old China was well received by readers. With its growing influence, the story of Zhi Garden has become increasingly well known. As a rare example of a Ming dynasty garden whose overall layout can be reconstructed from visual depictions, Zhi Garden fills a critical gap in the historical narrative of Chinese garden design.

To enable a wider audience to experience the flourishing aesthetics of private Chinese gardens at their peak, we devoted the next decade to an in-depth exploration of Zhi Garden. In 2022, we published Zhi Garden Album: A Portrait of Peach Blossom Spring (《止園圖冊:繪畫中的桃花源》) and Dreaming of Zhi Garden: Recreating a Painted Utopia(《止園夢尋:再造紙上桃花源》). These two volumes present high-resolution, full reproductions of all twenty paintings in The Zhi Garden Album, accompanied by detailed interpretations of the garden cultural, historical, and artistic significance.

In Chinese and English

by Liu Shanshan and Huang Xiao

Donghua University Press

Published: January 2022

by Huang Xiao and Liu Shanshan

in Chinese

Tongji University Press

Published: October 2022

The 17th century marked the pinnacle of classical Chinese private garden art, witnessing the emergence of numerous renowned garden designers and historically significant gardens. Unfortunately, many of these gardens have either vanished due to the ravages of war and the erosion of time, or undergone substantial transformation. As a result, reconstructing the gardens of the 17th century has become a crucial focus in the study of Chinese garden history. Among them, Zhi Garden stands out as a representative example of this golden era.

Zhi Garden was first established in the 38th year of the Wanli reign (1610). The name “Zhi Garden” (Garden of Restraint) is drawn from the poet Tao Yuanming’s verse in On Giving Up Wine (陶淵明《止酒》): “At last I realize that restraint is good; today I truly give it up.” The garden was designed by Zhou Tingce (周廷策), a prominent garden designer of the late Ming dynasty. Together with his father, Zhou Bingzhong (周秉忠), he belonged to one of the most distinguished families of garden makers during that time. Behind Zhi Garden stood the influential Wu family, who constructed more than 30 gardens during the Ming and Qing dynasties, earning them the reputation of a garden-making lineage. In modern times, the Wu family produced many cultural luminaries, including Wu Zuguang (吳祖光), Wu Zuqiang (吳祖強), and Wu Guanzhong (吳冠中), who continue to exert significant influence in the world of art and culture.

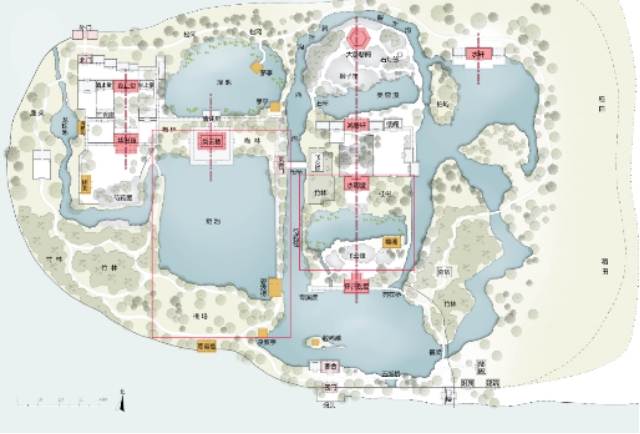

The physical structure of Zhi Garden has long since vanished, the garden faded into obscurity in the latter half of the 17th century and was subsequently forgotten by history. However, traces remain in the form of ruins, visual records, and historical texts. Drawing upon garden inscriptions, pictorial evidence, and topographical features, we have identified the original site of Zhi Garden to be located just outside Qingshan Gate, north of Wujin City in Changzhou. Today, the location of the garden site is found in Tianning District, Changzhou (常州市天甯區), although it has not yet undergone systematic archaeological excavation. The most significant historical material related to the garden is The Zhi Garden Album, which consists of one aerial view and nineteen detailed scenes. Together, these images comprehensively document the garden’s layout and its scenic architecture (Liu and Huang, 2024). The perspectives used in the album are based on real views within the garden, rendered through a realistic painting style that incorporates stylistic and technical adjustments by the artist. The Zhi Garden Album emphasizes visual correction grounded in lived spatial experience, offering a faithful representation of the actual scenery and enhancing the album’s function as a spatial guide.

Zhi Garden was designed as a suburban garden, distinguished by its unique approach route: visitors could arrive by boat from outside the city gate. The garden featured two main entrances, located on the north and south sides.

The overall layout of Zhi Garden was divided into four sections: the eastern, central, and western zones, along with an outer area. The eastern section served as the starting point for the garden tour, guiding visitors through a carefully orchestrated sequence of views. The central zone was characterized by expansive water features, creating a sense of openness and spatial depth. The western section was primarily residential, while the outer area on the eastern side seamlessly connected the garden to the surrounding countryside.

(Liyun Lou, literally “Pear Mist Hall”)

The owner acclaimed Zhi Garden as a garden “celebrated solely for the beauty of its water.” Situated beside the city moat at the junction of three rivers, the site incorporated an unusually rich variety of aquatic features. Because the terrain was relatively flat, dramatic vertical elements such as waterfalls were rare. Instead, the designer used rills, brooks, ditches, and channels, the linear waterways, to connect ponds, pools, lotus basins, and sunken hollows—broader expanses of water—thereby weaving an unbroken, serpentine network that animated the entire garden on a horizontal plane.

In Zhi Garden, rock and earth artificial hills ranked second only to water in importance. According to The Record of Zhi Garden, “the garden devotes three parts to earthen hills and one part to bamboo and trees.” The combined presence of rockeries and vegetation formed wooded hillscapes that covered roughly 40% of the garden, comparable in scale to its water features. Zhi Garden featured a full range of rockwork, from large to small: limestone rockeries, yellow stone mounds, earthen hills, terraced stone flower platforms, and individually placed ornamental peaks. Among them, Feiyun Peak (Flying Cloud Peak) within the wooded mountain grove was the most technically demanding to construct and best exemplifies the artistic mastery of the garden’s designer, Zhou Tingce. The artificial mountain appears as if it had flown down from the heavens and landed gently on an island surrounded by water. With no surrounding natural hills to borrow for visual continuity, the sense of its miraculous arrival is all the more striking.

The architecture of Zhi Garden formed a harmonious balance with the garden’s mountains, waters, and plantings, embodying a subtle interplay between the artificial and the natural. Although architectural structures occupied a relatively small proportion of the overall layout, they played a commanding role in organizing space, often serving as focal points along clearly defined axial sequences. This spatial arrangement reveals the principle of “the dynamic balance between the regular and the irregular” (qi zheng ping heng,奇正平衡) that underpins classical Chinese garden design.

Illustrated by Huang Xiao, Ge Yiying, and Wang Xiaozhu

Drawing on compelling reconstruction evidence and the garden’s exceptional historical significance, the Changzhou municipal government has decided to launch a project to rebuild Zhi Garden, with the aim of promoting the legacy of Jiangnan garden art and preserving local cultural heritage. This remarkable cross-border scholarly journey now holds the promise of bringing a once-imagined garden back into the real world. It signals the vast potential of international collaboration in the shared study and preservation of humanity’s invaluable heritage.

Author Biographies

Liu Shanshan Shanshan Liu is an associate professor in the History of Architecture at Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture in Beijing, China. She holds a doctorate in Architectural History and Theory from Tsinghua University. She has published several monographs in Chinese and English, including Garden Paintings in Old China (2012), Zhi Garden Album: A Portrait of Peach Blossom Spring (2022).

Huang Xiao is an associate professor at Beijing Forestry University and serves as the Secretary-General of the Research Center for Chinese Landscape Thought. His published works include The Vanished Garden: Zhi Garden of Ming-Dynasty Changzhou, Studies on Private Gardens in Ancient Northern China, and Architectural Atlas of Jiangsu and Shanghai.

References

[1] James Cahill, Huang Xiao, Liu Shanshan. The Immortal Landscape [M]. SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2012.

[2] Huang Xiao, Liu Shanshan. Dreaming of Zhi Garden [M]. Tongji University Press, 2022.

[3] Huang Xiao, Liu Shanshan. “The Poetic and Literary Context of Ming Literati Gardens: A Case Study of Wu Liang’s Zhi Garden” [J]. Art Panorama, 2023(02):122–126.

[4] Huang Xiao, Liu Shanshan. “The Subtle Delight of ‘Restraint’ in Wu Liang’s Zhi Garden” [J]. Journal of the China Garden Museum, 2021(00):21–26.

[5] Huang Xiao, Ge Yiying, Zhou Hongjun. “The Dynamic Balance of Order and Irregularity in Ming Garden Architecture: A Comparison of The Craft of Gardens and Zhi Garden” [J]. New Architecture, 2020(01):19–24.

[6] Huang Xiao, Zhu Yundi, Ge Yiying, et al. “View, Movement, Dwelling: Zhou Tingce and Flying Cloud Peak in Zhi Garden Garden” [J]. Landscape Architecture, 2019, 26(03):8–13. DOI:10.14085/j.fjyl.2019.03.0008.06.

[7] Zhou Hongjun, Surij, Huang Xiao. “Exploring the Water Management Strategies of Zhi Garden Garden in Ming-Dynasty Changzhou” [J]. Landscape Architecture, 2017, No.139(02). [8] Li, June; James Cahill. Paintings of Zhi Garden by Zhang Hong: Revisiting a Seventeenth-Century Chinese Garden. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1996