by Annette Giesecke

In the year 1936, author and theatre director Oliver Neal Gillespie (1883–1957) penned an impassioned eulogy of the town of Hastings and its environs. Titled “Highlights of Hastings — The Hawke’s Bay Garden of the Hesperides,” Gillespie’s piece appeared in The New Zealand Railways Magazine (Volume 11, Issue 6, September 1) and opened with a highly evocative description of the region’s landscape:

It is an old saying that the wealth of a land is in its soil. If it is truth, then Hastings is built upon treasure trove. As a matter of fact, the inevitable and rapid growth of the town has its tragic side. Each extra increment of its population spreads over and hides a rich lode. Such is the inordinate, the abounding and extraordinary fertility of the land of the district, that it amounts to sheer extravagance to cover it with paved roads, footpaths, homes and buildings, however handsome they may be. For aeons, the wandering rivers have been bringing in this huge, spreading series of flats, the countless riches of their gatherings. In many places, there are six feet of this black opulence from which any growing thing will spring with vivid life and swift strength. In a land of sunshine and warm and friendly rains, this area rightly claims many leadership rights. Its actual hours of sunshine place it along with Nelson and Napier among the world leaders in the blue sky’s greatest gift. Its rainfall, still, is ample for all purposes, but its rainy days might have been arranged on a limit fixed by tennis or cricket enthusiasts. It is an open air man’s paradise.[i]

There is a clear emphasis on the fertility of Hastings’ soil —“inordinate, abounding, and extraordinary” as he calls it — as well as on the region’s abundant sunshine and ample supply of water, all of which sustain a proliferation of plant growth. These noteworthy attributes, shared by Nelson and Napier, suffice to qualify Hastings as nothing short of “paradise.” Interestingly, Gillespie makes no further mention of the Hesperides’ garden but does later equate Hastings with Arcadia, a fabled, idyllic region in Greece, and with the Garden of Eden, especially Hastings’ Cornwall Park with its “sparkling sheets of ornamental waters”, “winding streams lined with roughcast edging interspersed with seats and novel bridges”, “long avenue of tall palms”, and “vivid green velvet of the lawns.”[ii] In what sense, then, was Hastings a twentieth-century Garden of the Hesperides, and what relation did that famous garden bear to Eden and Arcadia?

The Hesperides in Mythology

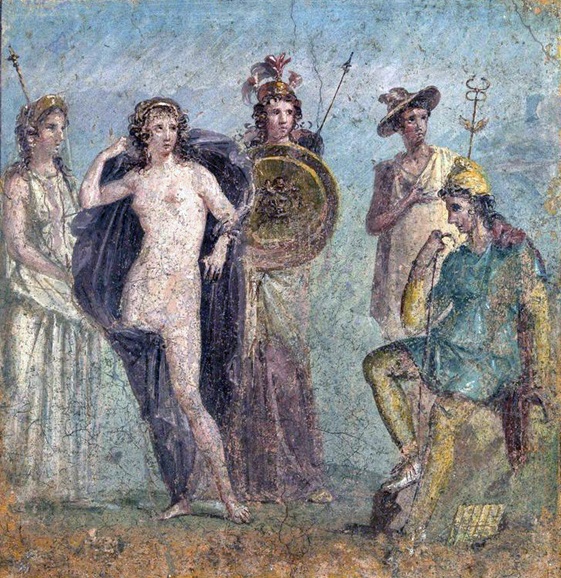

Attributed to Circle of Meidias Painter [Greek (Attic), active 420 – 390 B.C.]. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, inv. 91.AE.9, open access.

In classical mythology, the Hesperides were nymphs entrusted with tending the trees that yielded the golden apples so famous in classical mythology. The Hesperides were between four and seven in number, and their names are variously given as Aegle, Erytheia, Hestia, Arethusa, Hespere, Hesperusa, and Hespereia. Accounts of their birth and the location of their garden, the Garden of the Hesperides, are also various. The poet Hesiod (lived circa 725 BCE), an early source, names the elemental deities Nyx (“Night”) and Erebus (“Darkness”) as their parents, but later accounts state that their parents were either the sea god Phorcys and his sister Ceto; or Zeus, king of the Olympian gods, and Themis, the personification of justice; or the second-generation Titan god Atlas, who supported the heavens on his shoulders, and Hesperis, daughter of Hesper, the evening star. The location of the Hesperides’ garden, equally difficult to pin down, was said to be either in North Africa, specifically what was called Libya in antiquity, near the Atlas mountains (modern Morocco); or in the westernmost Mediterranean on the shores of the river Oceanus; or, alternatively, in the lands of the Hyperboreans, in the far east or to the far north, all of these locations being at the “ends of the earth” as it was then conceived.

As for the golden apples, the trees that produced them were presents made by the Earth goddess Gaia to Hera, queen of the gods, on the occasion of her marriage to Zeus. The apples were sources of immortality, and thus highly prized. One of these apples ostensibly caused the Trojan War: the goddesses Hera, Aphrodite, and Athena all desired a certain golden apple inscribed with the words “for the fairest.” The Trojan prince Paris was selected to decide who the fairest among them was—an impossible choice to make objectively. He chose Aphrodite, who had also offered him a most enticing bribe: Helen, the loveliest woman in the world. Hera, meanwhile, had offered empire without end, and Athena offered success in war. Aphrodite, however, knew the philandering young prince Paris best. He was notorious for his enthusiasm for women. It was accordingly Aphrodite who was awarded the apple. Paris now faced a challenge in claiming his prize, as Helen was married to Menelaüs, the Spartan king. When Paris absconded with her to Troy, a thousand Greek ships, carrying Greece’s elite warriors, sailed in hostile pursuit. The Greeks besieged Troy for a period of ten years until that city, at long last, fell, consumed by flames when the Greeks, hidden in the belly of the Trojan Horse, emerged from their hiding place with torches and swords in hand.

The golden apples that Aphrodite supplied to young Hippomenes in order to help him win the hand of Atalanta were also said to be from the Hesperides’ trees. Atalanta wished to remain a huntress, unmarried and a virgin like the goddess Artemis, but numerous men pursued her. Conceding to her father’s entreaties that she consider marriage, she agreed to marry whoever could outrun her. Many unsuccessfully attempted to win her hand and paid the penalty for loss with their lives. Still, one, undaunted, prevailed. This youth, Hippomenes, a great-grandson of the god Poseidon, called upon the goddess Aphrodite for aid, and she responded, bringing him three golden apples from her sanctuary on the isle of Cyprus. The race commenced, and Meleager threw one apple after another out to the side of the race course. Atalanta could not resist the apples, retrieving each of them in turn. Atalanta’s dash after the last apple allowed the youth to win the race and so win her as bride. Atalanta developed affection for her new mate, but the couple’s joy did not last, for in his excitement over his victory, Hippomenes had forgotten to thank Aphrodite. The angry goddess drove him wild with passion, and consequently, they defiled a temple of the goddess Cybele with their lovemaking. For this Cybele punished them by transforming them into lions that she then fastened to the yoke of her carriage.

Finally, there was the saga of Hercules and the golden apples. As the eleventh of his famous Twelve Labours, Hercules was told by the evil king Eurystheus to bring him apples from the Hesperides’ garden. Not knowing the garden’s location, Hercules first consulted the nymphs of the river Eridanus, who in turn directed him to the sea god Nereus. Hercules seized Nereus, who possessed prophetic powers, while he was asleep and held him fast while the latter repeatedly changed shape; Nereus would only prophesy under compulsion. Directed by Nereus, Hercules commenced his journey and, on the way, came upon the Titan god Prometheus, whom he released from the torment of having his liver eaten away eternally by vultures. From Prometheus Hercules received further advice regarding the accomplishment of his labour: he should ask Atlas, the Hesperides’ neighbor, to fetch the apples in his stead. This Hercules did, asking Atlas to bring the apples in exchange for relieving him, temporarily, of the heavens’ burden. Not surprisingly, Atlas was not keen to resume the onerous task of supporting the heavens on his shoulders, but Hercules tricked him by asking for a temporary reprieve in order to place a pillow on his shoulders as a cushion. According to a variant of this story, which did not involve Atlas, Hercules slew the sleepless, hundred-eyed dragon Ladon that guarded the apple trees and retrieved the apples himself. In any event, Hercules brought the apples to Eurystheus who ultimately returned the sacred apples to him. Hercules, in turn, gave the apples to Athena to return to the Hesperides.[iii]

To Be Continued (in Parts II and III): The Hesperides’ Garden and its Afterlife: Exotic, Fertile Place; Were the Golden Apples Not Apples at All?

Notes

[i] The New Zealand Railways Magazine, Volume 11, Issue 6 (September 1, 1936), page 9.

[ii] Page 10.

[iii] For more detail detail about the Greek gods, goddesses, heroes, and heroines, see Annette Giesecke, Classical Mythology A to Z (2020: Hachette, Black Dog and Leventhal, Running Press).