by Ian Duggan, Te Aka Mātuatua – School of Science, The University of Waikato

New Zealand had the occasional famous visitor in the mid-1920s. For Anna Pavlova, the famed Russian ballerina and dessert inspiration, several hundred newspaper articles were devoted to her visit to this country in 1926. Adventure novelist Zane Grey also visited in 1926, and in 1927 there was a Royal Visit by the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King George VI and Elizabeth). In 1928, however, a huge number of column inches were reserved for Dr Arthur William Hill, the Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Hill had joined Kew as Assistant Director under Sir David Prain in 1907, and eventually succeeded him as Director in 1922. His New Zealand visit was initiated five years later, in 1927, when the Empire Marketing Board ear-marked £4OOO of its revenue a year over five years to permit the Director of Kew, or his assistants, to travel to co-operate in development work in the Empire.[i] Hill stated that the idea of such travel arose out of a conversation with the secretary of the Empire Marketing Board, who, at a luncheon, had asked him to suggest some means whereby the Board could assist botany in the Empire. Hill thus suggested help could be provided through the provision of funds sufficient to send a man—himself, for instance—on tour to whatever countries required assistance with their problems. He also suggested that the fund would need to include provision for the appointment of an assistant director, who would carry on ‘at home’ in his absence.[ii] The first country visited under the new scheme was British Guiana, while another man had been sent to the Malay States to study banana disease, and yet another curator had been sent to Java, Ceylon and Singapore to study tropical vegetations under natural conditions.”[iii] New Zealand’s Auckland Star newspaper described the purpose of the visit:

“If the Gold Coast wants a suitable cocoa plant, if Fiji wants to know what disease is affecting the banana crop, if Australia wants to grow cricket bats, or if New Zealand should wish to start the beet sugar industry, Kew undertakes to supply the plants and to answer questions about them”.[iv]

Then it was Hill’s turn to visit New Zealand, taking advantage of an existing invitation to visit Australia.[v]

Botanist Leonard Cockayne, one of New Zealand’s most influential scientists, played a major role in organising this visit, and with E. Phillips Turner, Secretary of Forestry, he accompanied Hill through his New Zealand tour.[vi] In letters to Cockayne prior to his visit, Hill suggested he would spend a fortnight in New Zealand, and asked for suggestions on where to visit: “All too short a time, I fear… there is nothing I should enjoy more than seeing the New Zealand botanists and something of the vegetation of the country”, Hill wrote. Cockayne concurred: “It was both exciting and most pleasant news to learn that you propose to visit this country next January. But a fortnight is far too short a time. Possibly in a well directed month you could see a good deal of New Zealand vegetation and also the economic botany (forestry, agriculture, horticulture)”. Among Cockayne’s major contributions to botany were in his theories of hybridisation[vii], and with an element of self-interest he responded: “Above all, I want you to see some of our hybrid swarms”.[viii]

Years later, Hill reflected on his experience of travelling with Cockayne, at a time when the New Zealand scientist was 73: “No matter whether we were in a crowded train or wedged in the back seat of a motor car, he would discuss abstruse botanical matters or bring forward knotty points as to hybrids, or what was meant by such and such a species. Then his son Alfred would join in with a totally opposite point of view and a fierce altercation, proving quite harmless, would ensue – an outsider might have thought blows would follow! – and all would end happily”.[ix]

The New Zealand Tour

Before the tour even started, controversy arose. In early January 1928, the itinerary for his three-week visit to New Zealand was mapped out and announced. Hill was to make:

“Visits to the kauri forest, or Rangitoto Island, and the Domain, Auckland; to the forestry plantations and native forests at Rotorua; to Taupo and National Park; and to the flax swamps and pastoral lands of the Manawatu. While in Wellington Dr. Hill will hold consultations with the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, visit Wainui-o-mata in company with the director of parks and reserves, and be the guest of honour at a reception to be tendered by the New Zealand Institute of Horticulture in the Concert Chamber of the Town Hall, where a special display of New Zealand flowers will be given. In the South Island Dr. Hill is to visit Christchurch, and will inspect the forest services at Hanmer and the plantations of the Hon. Sir R. Heaton Rhodes. Other visits include calls at Arthur’s Pass, Hokitika, and Nelson. A walk from Arthur’s Pass to Otira is contemplated”.

Ominously, reports on the itinerary ended with the note: “It is doubtful whether time will permit of a visit to Dunedin”.[x]

On 7 January, the Otago Daily Times – clearly stung by the snub of the city – ran a piece titled “No Time for Dunedin”. “And where,” it asked, “does Dunedin come in? It is a pertinent inquiry, and the answer is unfortunately discouraging. Apparently Dunedin is not to come in at all. In the words of the message from Wellington, in which Dr Hill’s movements in the Dominion between his arrival on January 20 and departure on February 13 are circumstantially indicated: “It is doubtful whether time will permit of a visit to Dunedin.” About the phrase there is a touch of ingenuousness. The manner of it is perhaps suggestive of a certain delicate concession to the susceptibilities of the South. There is an implication of official sympathy and of regret that we are to be disappointed. For what is perhaps to be interpreted as really quite a friendly gesture we should possibly be grateful. For, after all, upon this occasion there is at least definite recognition of the existence of Dunedin, and as often as not even that is entirely lacking in intimations of tours arranged for visitors to this country from overseas. The programmes are prepared in Wellington, and more often than not the South Island is apparently not regarded as of sufficient economic importance to warrant the recommendation on the part of officialdom that tourists or missioners from other countries should occupy any part of their time in visiting it. Consequently, to have mention made of Dunedin in connection with Dr Hill’s itinerary should perhaps be soothing to this community, though its effect in that way may be a little difficult to detect.”[xi]

Things escalated. Within days, a meeting of interested bodies was held to protest against the omission of Otago and Southland, chaired by Mr Thomas Sidey, Liberal M.P. for Dunedin South, and including members of their City Council, the local branch of New Zealand Institute of Horticulture, the Chamber of Commerce, the Expansion League, the Otago A&P Society, the Dunedin Horticultural Society, Nurserymen’s Association, and the Amenities and Town Planning Society. Among them was Kew-trained horticulturist David Tannock, and superintendent of Dunedin’s city reserves, who felt it “a conspiracy”. He believed that there was not the slightest doubt that Dr Hill would be asked by the Government to report on the desirability of a national botanic garden, and he considered that Dunedin was especially suited for such a purpose. “I consider that Dr Hill has been deliberately prevented from visiting Dunedin”, Tannock stated, “so that he cannot see what Is being done. Botanical work is negligible elsewhere—it is nil in Auckland and practically nothing in Wellington. There is a more complete collection of healthy plants in private gardens in Dunedin than anywhere else in New Zealand, and we have organised a system of collecting, establishing, and exchanging plants, and we have tried to maintain a system of exchange with other parts of the world”.

The group framed a resolution of protest. Among their arguments were “That the inclusion of Dunedin is especially important, seeing that it is the only city in the dominion that has in its botanical gardens, a very large and representative collection of New Zealand’s alpine vegetation and many plants from the Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes, and Chatham Islands”. “That the Dunedin Botanical Gardens are making a systematic effort to carry out the function of a true botanic garden—namely, by maintaining a system of exchange of plants and seeds with botanical gardens and cultivators in other parts of the world, and by establishing as complete a collection of the vegetation of all parts of the world as possible, and adopting a simple system of botanical and geographical classification by training young men and women in gardening and forestry.”[xii]

Ultimately, the protestations worked. Hill’s itinerary was revised, and it was announced he would spend one and a half days in Dunedin after leaving Christchurch.[xiii] Nevertheless, fate intervened in Dunedin’s favour regardless, when his steamer, Manuka, was diverted due to a sick fireman”. Hill had left Melbourne bound for Milford Sound and Wellington, intending to start his journey through New Zealand with an inspection of Nelson and Westland. With the steamer heading for Milford, one of the firemen became seriously ill. Luckily for the fireman, one of the passengers included a Dr Gordon, who operated surgically at 12 o’clock that night, and the vessel’s course was changed, being put at her fastest pace on the way to the Bluff. At Bluff some New Zealand friends of Dr Hill suggested that he should alter his itinerary and step ashore at Bluff. As such, his first night was spent in Invercargill, and he went to Dunedin by the express train the next morning”.[xiv]

Placating Dunedin, Hill had many nice things to say about the city, stating that he did not think there was a much more beautifully situated town, with its wealth of greenery, that it was splendidly laid out, and that the reserves in the heart of the city were quite unique. “The pioneers had shown a wonderful foresight in laying out the city, with its reserves and fine areas of native bush”. Dr Hill added that he had been very favourably impressed with the general tidiness and cleanliness of the city and its surroundings, showing that the citizens respected their property. This was especially apparent, as nobody knew he was to make a visit that morning, so that there could be no general tidying-up because he was visiting. He generally praised Dunedin’s gardens, where he thought there was a wonderful collection of native trees and shrubs, with the collection in some ways far more interesting than that seen in any gardens he had visited in the southern hemisphere. Dr Hill went on to refer to the great value of the native trees and shrubs, and said that the real object of botanical gardens was to educate the public – a point he commonly made clear during the trip. He did not think it likely that there was any collection of native trees in New Zealand to compare with those in the Dunedin Gardens. The only criticism was that he thought it was a pity that telegraph poles were allowed to remain in the gardens, being unsightly, and out of place in that setting. He was also surprised to see what Mr Tannock had accomplished with the small staff at his disposal, and he considered he should have a larger number of men, because he was developing gardens that were of very great importance to the Dominion.[xv]

Although Hill visited a number of other areas in the country, the remainder of this blog will concentrate on a single theme where friction was developed during, and following, the tour – the development of a National Botanic Garden. Needless to say, he was generally on a charm offensive as he travelled. For example, he declared Oamaru Gardens to be among the most beautiful he had seen on his overseas travels, where he was especially pleased with the Peter Pan statue and its setting.[xvi] On visiting Otari Reserve/Willton’s Bush, in Wellington, he stated he considered it an ideal place for an open-air plant museum.[xvii] More general praise followed: “To see the orderliness and tidiness of the people in New Zealand has been the greatest pleasure to me” he said, speaking at the Auckland University Hall. “Here in the City of Auckland I find gardens planted right to the edge of the footpath, with no fear of people taking anything. It will be very nice to hold you up as an object lesson to the people at home. Our public is not as well-behaved as the New Zealand public.”[xviii] He built on this elsewhere, stating: “What astonishes me is the neatness of everything. One wonders where all the old newspapers and orange peel go to. I shall certainly tell people about it when I get back to England.”[xix]

A National Botanic Garden

In Wellington, the first mention of a National Botanic Garden was mooted by Dr. James Allen Thomson, which became a theme throughout Hill’s tour. Thomson stated that he hoped that the establishment of such a garden would follow Dr Hill’s visit. However, Hill immediately noted that the word “National” raised some difficulties and would lead to potential jealousies, and likened it to a situation in South Africa where rival gardens had been established by two cities. Nevertheless, Hill proposed that a southern garden might be developed in Dunedin and a northern garden in Auckland, for in Dunedin things could be grown that would be impossible in Auckland, and vice versa. He felt there might be a scientific head or director linking the two together as a national institution, joined by two curators, one in each city.[xx] In doing so, local jealousies might be overcome.[xxi]

In Auckland, he even suggested a possible location for the northern garden: “Exactly where it should be established is a local matter, and not one in which I should interfere. I did, however, see a very nice place, this afternoon in Cornwall Park, where it should be possible to develop good botanic gardens”. Still aware of the local parochialism, he noted: “I will warn you on one point because I have heard mention of a ‘national’ botanic garden for Auckland. If you carry on with that idea you are not only likely to get into hot water with other centres in New Zealand but you will be taking a wrong course from a scientific point of view. It is impossible for you to grow here in the North some of the things that grow in the South, just as down there they cannot grow some of the plants that you grow here.” Again, he reiterated that if there was to be a National Botanic Garden, it would be best to divide it into two parts, one in the North and one in the South.[xxii]

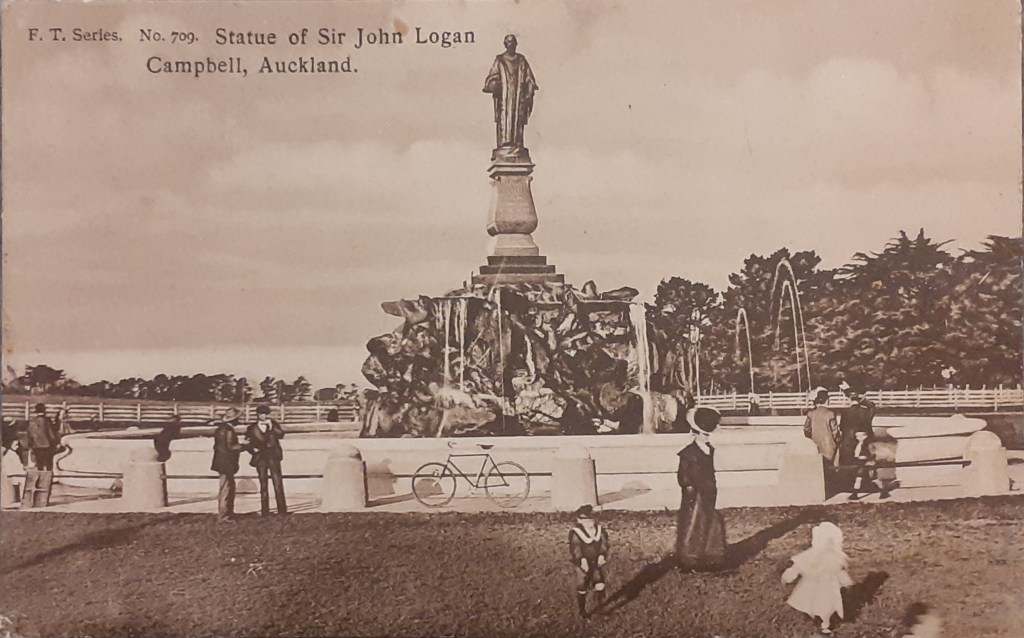

Auckland newspaper The Sun quickly pointed out why Cornwall Park would not be a good option, however: “The public could not be allowed to picnic beneath valuable specimen trees, nor, small boys permitted to climb their leafy heights in search of birds’ nests. Therefore, though the visitor [Hill] saw in Cornwall Park an ideal location for the type of institution he recommends, his choice is hardly likely to be endorsed by the citizens of Auckland. Cornwall Park was presented to the city in 1901, by Sir John Logan Campbell, and its 230 acres form an unsurpassed area of park land. The donor’s specific stipulation set the land apart for the people of the city, and the establishment of a botanic reserve would therefore introduce inevitable conflict with the people’s rights.”[xxiii]

Following Hill’s departure from the country, a summary report to government provided in April crystallised his thoughts. This provided some detail that contrasted with his public statements. In it he criticised New Zealand’s existing Botanic Gardens: “Botanic Gardens do not exist in New Zealand except in title and by Act of Parliament”, he stated. “The present gardens are really public pleasure gardens, with a good horticultural display, which is in no sense a botanical arrangement.” Here, he reiterated that New Zealand was in need of a National Botanic Garden, but owing to the differences with regard to climate between the North and the South Islands, there was not any one spot could be chosen adequately to represent the flora of New Zealand to full advantage. Further, he noted the difficulty in that each of the four main centres naturally regards its own botanic garden as a place of considerable importance, and he feared that, were any one of the botanic gardens now in existence chosen as the seat of the National Botanic Garden, considerable jealousy and friction might be aroused. Again he proposed a National Botanic Garden in two parts, with one centred in Dunedin, where the high Alpine plants could be grown, while he proposed the northern garden be situated in either Wellington or Auckland. Again he noted that the leaving out of any of the four main centres may lead to difficulties that would prevent what he regarded as an ideal scheme from being a workable proposition. With that being the case, he felt that it may be better to select Wellington as the headquarters of the Dominion Botanic Garden, and consider the gardens of Dunedin, Christchurch, and Auckland as branches of the Dominion garden.[xxiv]

The current gardens came under some criticism, being not what Hill considered to be ‘real’ botanic gardens: “The nearest approach to a botanic garden is the one at Dunedin, but that fulfils the proper functions of a botanic garden only to a small extent. At Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin there is a fairly representative display of the native flora, but the native plants are not displayed in any botanical or biological manner so as to be of real educational value, nor are they properly labelled. The present gardens are really public pleasure gardens, with a good horticultural display, which is in no sense a botanical arrangement. At Dunedin, some efforts have been made in the right direction, but labelling everywhere is poor. To be of real use, the scientific and English or Maori names of plants should be given as well as their natural families, and their country of origin”. His greatest criticisms were directed towards what he called “a sad waste of money” in some centres in the erection of costly structures called “winter gardens” – these “housing a very poor collection of plants of no botanical interest, and of very little horticultural value”. Nevertheless, he believed they might be made of interest under the care of a scientific man.”[xxv]

A full report of Hill’s visit was printed in booklet form by the Government in June, which led to widespread resentment and negative reaction. Christchurch’s The Star reported on the “Severe criticism of the Cuningham Winter Gardens in the Christchurch Botanic Gardens”, as well as those in Auckland, where Hill was “strongly critical of the winter gardens that have been erected in these cities”. “What I have said about the present gardens being really public pleasure gardens is well illustrated by the Christchurch Botanic Gardens and by the Domain Gardens at Auckland”. “In both there has been a sad waste of money in the erection of winter gardens—costly structures, housing a very poor collection of plants of no botanical interest and of very little horticultural value. The plants displayed could have been grown in any small greenhouse, as the ugly and large structures contain only a senseless repetition of a few comparatively uninteresting plants”. Hill’s criticisms were stated to be “strongly resented” by Mr James Young, Curator of the Christchurch Botanic Gardens, who stated that it was quite uncalled for and was absolutely unjustifiable from a man of Dr Hill’s standing. “I do not think Dr Hill was brought to New Zealand to indulge in that kind of criticism”, Mr Young added. “He was brought here, I understand, to report on matters of scientific interest, not to try and scandalise what is being done in Auckland and Christchurch… The Cuningham Winter Gardens have increased the popularity of the gardens fifty-fold, and, moreover, they are a gift to the city and have not cost the Domain Board a penny.” He continued, “I don’t happen to be a Kew-ite but I come from Edinburgh and Glasgow, which are just as good places. It is absolute nonsense to say that the plants in the Winter Gardens could be grown in any greenhouse. Winter gardens are generally two stories high, and the one in the Christchurch Gardens follows practically the same design as the Winter Gardens in Glasgow. It contains some slashing good stuff in spite of all Dr Hill has to say”. Mr G. Harper, chairman of the Domains Board, was also invited to comment on Dr Hill’s criticism. He said that the board looked at the matter from a different point of view from Dr Hill, regarding the Winter Gardens as the greatest attraction to the Gardens. “Dr Hill was a scientific man and he looked upon these matters from the scientific point of view.”[xxvi] Mr H. J. Duigan, Dominion president of the New Zealand Real Estate Institute, and a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society of England, felt that the criticism levelled by Dr Hill was wrong both in purpose and intent. He stated that while Dr Hill was a very eminent man, he had looked at the park from the point of view of its being a botanical or horticultural laboratory, and had overlooked the fact that it was laid out primarily with the object of giving pleasure to thousands of people.[xxvii]

A month later, the negative responses to the reports continued. From a seemingly fiery meeting of the Association of Parks and Gardens Superintendents of New Zealand, members viewed with disfavour some of the statements contained in the report. “Dr. Hill had characterised as a sad waste of money the erection of costly winter gardens, both at Christchurch and Auckland”. The chairman, Mr D. Tannock of Dunedin, who had earlier been upset by Dunedin’s omission, believed that a garden devoted entirely to botanical species would be of little interest to the general public. “This report of Dr. Hill leads us nowhere”, said Mr McPherson, of Invercargill: “Dr. Hill has overlooked the fact that conditions in New Zealand are vastly different those prevailing in other countries. Our public gardens serve a dual purpose — although essentially gardens they are also recreation grounds. The public wants a bright display, and it is our duty to fulfil requirements in this respect; at the same time educating the public on the scientific side”. “The remarks of Dr. Hill in regard to the labelling of plants are a distinct reflection on the superintendents”, continued Mr McPherson. “I, for one, am anxious to do this, but where is the money to come from? Dr. Hill does not enlighten us in this connexion — he has taken too much for granted. As to Dr. Hill’s suggestion that the Botanic Gardens should be controlled from Wellington, I doubt very much whether such a scheme is feasible in New Zealand, where the gardens are controlled by the municipalities”. Mr J. Young of Christchurch, who had visited the gardens at Kew, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Dublin, declared he thought that the gardens of New Zealand were equal to the best in the world, which was met by applause from the group. Further reported comments came from Mr J. E. Mackenzie, of Wellington, who stated “I’ve often wondered, why Dr. Hill ever came to New Zealand”, while Mr McPherson declared that Dr. Hill’s visit had been badly arranged from start to finish. MacPherson believed “It was a great pity that he was not given a better opportunity of meeting the men responsible for bringing the gardens of the Dominion to their present high standard of efficiency”. The chairman, Mr D. Tannock, concurred, stating: “That’s what he should have done instead of gadding over mountains and being taken about in motor-cars, wasting valuable time. Dr. Hill could have seen all the alpine plants in our Botanic Gardens.”[xxviii],[xxix]

But was this reporting accurate? Soon after, MacKenzie, at least, was quickly backpedalling, blaming the newspaper for mis-representing the conference. To the Editor of the Evening Post, he wrote: “Your criticism in connection of the New Zealand Association of Gardens, Parks, and Reserves Superintendents in connection with the above proposal has been called to my attention. Your information, I presume, is based on a report… copied out in ‘The Post’, which gives quite a wrong impression of what was in the minds of the speakers at this conference.” “Your inference that the conference wished to disparage Dr. Hill is quite contrary to fact…”. “When the itinerary of Dr. Hill’s visit to this country was drawn up, the main feature was not to visit the Botanical Gardens, but to let the distinguished visitor see as much of the natural beauty of the country as possible. The main reason of the visit, I have been advised, was Dr. Hill’s desire to study the native hybrids of this country, and to meet Dr. L. Cockayne, F.R.S., whose research work in this connection is of world value and interest.”[xxx]

Nevertheless, the negative feedback reached Hill. On hearing this criticism, Hill responded at length in January 1929: “I am very sorry to learn that some parts of my report relating to ‘Botanic Gardens’ have been misunderstood and have thus given rise to a good deal of adverse criticism. I was very much impressed by the beauty of the gardens which I visited, and I saw those at Nelson and Palmerston North in addition to the six mentioned in my report. As I also visited some nurseries, experiment stations, the forestry plantations both in the North and South Islands, and the Cawthron Institute, I think it was hardly fair of one of the horticulturists, whom I had the pleasure of meeting, to say that I wasted my time in ‘gadding over’ mountains and being taken about in motor-cars. I doubt if any botanist has ever been given so splendid an opportunity of seeing the various aspects of the vegetation of New Zealand as I was, and of thus being put in a position to assist botanical enterprise in the Dominion whenever called upon to do so. With regard to my remarks about a National Botanic Garden, the garden superintendents have quite misunderstood the purpose of my remarks. I very much admired the various gardens I visited, but the point of my remarks about the establishment of a National Botanic Garden was, firstly, to consider the proposals for such a Botanic Garden which had already been made in the Dominion, and, secondly, to put forward my own suggestions how such a desirable project might be best brought about. I beg to submit that it was essential to discuss how far any of the existing gardens in the principal cities of the Dominion could be considered, either as fully ‘national’ or wholly ‘Botanic’ in their aims and functions. That a botanic garden should make a fine horticultural display is both very necessary and perfectly legitimate, but this should not be done at the expense of botanical functions. In order that a garden should be a real botanic garden, a large part of its area must be devoted to a collection of plants, systematically arranged and well labelled, so that it can be of the greatest educational value. With a flora of so much interest as is that of New Zealand, a fine collection of the native plants, together with related plants from adjacent countries is, I consider, a highly desirable object… My critics, who ought to know, seem to forget that the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew and Edinburgh and the Glasnevin Gardens, Dublin, serve a dual purpose; since they are pleasure grounds for the enjoyment of the public as well as scientific institutions, and l was anxious to see more attention paid to the latter function in the New Zealand botanic gardens. As the chief critics of my remarks appear earnestly to desire to have a national botanic garden, established, I must confess, I rather fail to understand some of their adverse criticisms”.

Interestingly, he added a note that his report was never intended for widespread consumption: “In conclusion I should add that I was under the impression my report was in the nature of a private and confidential document, and therefore it was not written with a view to publication… I do not, however, feel on rereading my report that I have reflected unfavourably on any of the beautiful gardens in the Dominion when it is remembered that my reference throughout was to a botanic garden in the real meaning of the term”.[xxxi]

Ultimately, New Zealand never did get its National Botanic Gardens.

[i] Empire Marketing Board. Activities in Research. New Zealand Herald, 4 April 1927, P 7

[ii] The New Gardens. Waikato Times, 9 February 1928, P 5

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] A Distinguished Visitor. Auckland Star, 6 February 1928, P 6

[v] Evening Post, 21 October 1927, P 9

[vi] A. D. Thomson (1980), Annotated summaries of letters to colleagues by the New Zealand botanist Leonard Cockayne. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 18: 405-432, DOI: 10.1080/0028825X.1980.10427256

[vii] https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3c25/cockayne-leonard

[viii] Thomson A.D. (1980), Annotated summaries of letters to colleagues by the New Zealand botanist Leonard Cockayne. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 18: 405-432, DOI: 10.1080/0028825X.1980.10427256

[ix] Hill AW (1935), Leonard Cockayne 1855–1934. Obituary Notices of the Royal Society of London 4: 443–457.

[x] Economic Rotary [sic], Poverty Bay Herald, 7 January 1928, P 7

[xi] Otago Daily Times, 7 January 1928, P 10

[xii] Evening Star, 10 January 1928, P 3

[xiii] Evening Star, 14 January 1928, P 6

[xiv] Dr Hill Here. Evening Star, 23 January 1928, P 6

[xv] Otago Daily Times, 24 January 1928, P 10

[xvi] Provincial News. Otago Daily Times, 25 January 1928, P 11

[xvii] A Plant Reserve. Dominion, 26 January 1928, P 10

[xviii] Local and General News. New Zealand Herald, 7 February 1928, P 8

[xix] Botanist’s Visit. New Zealand Herald, 7 February 1928, P 11

[xx] National Botanic Garden. Press, 27 January 1928, P 3

[xxi] National Gardens. Evening Post, 27z January 1928, P 6

[xxii] Botanic Gardens. Auckland Star, 7 February 1928, P 10

[xxiii] The “Uppos” are Coming! Sun (Auckland), 7 February 1928, P 8

[xxiv] Botanic Gardens, Evening Post, 2 April 1928, P 13

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] “No Value and Little Interest”. Star (Christchurch), 13 July 1928, P 4

[xxvii] Star (Christchurch), 20 July 1928, P 10

[xxviii] Botanic Gardens. Press, 22 August 1928, P 10

[xxix] Dr Hill’s Report Meets Criticism. Star (Christchurch), 22 August 1928, P 6

[xxx] National Botanic Gardens. Evening Post, 27 August 1928, P 8

[xxxi] Botanic Garden. Evening Post, 19 January 1929, P 6