by Ian Duggan, Te Aka Mātuatua – School of Science, The University of Waikato

Much was written in the newspapers about the 1928 visit to New Zealand by Dr. Arthur William Hill, the Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. As covered in Part 1 of this blog, there was an outcry in Dunedin at not being a destination in his initial travel itinerary, and further provincialism came to the fore in his push for a National Botanic Garden of New Zealand. In this blog, we look at how Hill’s opposition to a road on Rangitoto Island stirred up emotions in Auckland. Hill’s visit to Auckland was brief, spanning only the 5th and 6th of February 1928, and his visit to Rangitoto Island was even shorter – totalling an hour. But that hour led to much debate in New Zealand’s newspapers.

A Road on Rangitoto

The construction of a road on Rangitoto was put forward at a meeting of the Devonport Borough Council in February 1925, when business of the Rangitoto Domain Board was discussed, three years prior to Hill’s visit. It was proposed that the construction of a road should encircle the base of Rangitoto, thereby opening up parts of the island that at the time were inaccessible[i]. Cost, however, was an immediate issue, though plans were made to circumvent this problem:

“Ample material is available on the island for road construction, and the principal cost would be the labour. Although the Domain Board has a substantial credit balance, it would not be sufficient to undertake the outlay. The Minister for Justice is to be communicated with asking that a prison camp be established on the island and prison labour used for constructing the road”.[ii]

Soon after, a visit was paid to the island by officials of the Prisons Department, including the Inspector-General of Prisons. The roadway was proposed to commence at the wharf and skirt the base of the island to beyond Rangitoto Beacon, from where a road would be continued up the side of the island to connect with an existing track leading to the summit. The Inspector-General stated that he was favourably impressed with the proposal and he would submit his recommendation to the Minister for Justice, Sir James Parr.[iii]

In June, “after long and careful consideration”, Parr agreed that the road could be made by employing a gang of short-sentence prisoners. “The proposed road,” said Sir James, “will be six miles in length, and will be suitable for both pedestrian and motor traffic. When completed it should prove of very great benefit to the citizens of Auckland, and to the community generally, as it will provide easy access to a vantage point from which a magnificent view of the Waitemata, the city and its environs, and a wonderful land and seascape eastward is obtainable”. Further, “the work would provide for relieving overcrowding in prisons in Auckland, and a means of most usefully employing well behaved prisoners, whose sentences were too short to warrant their being sent to one of the Prisons Department farms”. He continued, “The scheme is rendered particularly suitable for the employment of prisoners… by reason of the fact that owing to the isolated locality of the work, the men will be far removed from the public gaze… A gang of some twenty prisoners will be employed on the job, maintained… by the Prisons’ Department”.[iv]

Questions were quickly raised about the scheme by the New Zealand Herald, however: “But are the board and the Minister quite certain that the building of a road to the top of Rangitoto is the best way of using the prison labour which the Minister proposes to supply? After the road has been made, how are the motors to reach it? …The great majority of people will regard the whole undertaking as a ridiculous extravagance. If more prison labour is available than can be usefully employed on tree-planting, sawmilling and land development, surely the department can find work for it more urgent and necessary than the roading of Rangitoto Island. There are hundreds of miles of national highways whose needs are clamant, and the employment of prison labour upon them… would be vastly more sensible than using it to provide an inaccessible highway for an entirely illusory motor traffic to the top of Rangitoto.”[v]

The Auckland Star presented similar views: “But to go to the trouble and expense of making a motor road on this island, which can be reached by motorists only after a long trip on a ferry steamer, is one of the wildest proposals we remember… The delights of the Waitakeres, for example, need better roads to make them accessible to Aucklanders, and those wonderful hills have the advantage over Rangitoto of being connected with the city by land”.[vi]

In a letter to the Auckland Star, an AJ Nagle agreed: “Many thanks for your leader protesting against a motor road to be constructed on Rangitoto. One half of the charm of that unique island is due to the fact that whilst there, one is out of sight and sound of the ubiquitous motor, and I think many people will fail to see how its attractions are to be increased by the introduction of these odorous juggernauts. The Minister concerned in the matter, naively remarked that the proposed road would be for the benefit of pedestrians as well as motorists. As the present track to the summit is some two miles in length, and the new road is to lie six miles long, it is obvious that the road is worthless to those who venture afoot”.[vii]

Others, however, were for the scheme: “I was glad to see in my “Star” to-day that the Government is going to build a fine road up to the summit of beautiful Rangitoto”, wrote Mr. JA Lee of Auckland East”.[viii]

The Minister for Justice, Sir James Parr, was surprised by criticisms of the scheme. “Really, I fail to see why anyone should wish to make fun of a road on Rangitoto… It is easy to say that the road will be of no use for motor-cars… but what about motor-buses running from Rangitoto Wharf to the summit? When there is a fine road six miles long, with perhaps a rest house and tea kiosk at the summit, there will be no better holiday resort near Auckland. Imagine a broad level road running round the shore from the wharf to the beacon, with pretty seaside cottages dotted along it… To say that the men could be better employed in improving roads in the Waitakare Ranges did not affect the question at all. The roads in the ranges were controlled by local authorities with rates at their disposal, and the Auckland City Council, which held large areas of land there, should be well able to contribute to the upkeep. Rangitoto was vested in a body which had almost no funds and the work would be entirely for the benefit of the public in general”. He felt sure that the people of Auckland would fully appreciate the value of the road when it was completed.[ix]

It was decided that fourteen prisoners – only short-sentence, good conduct men – would be employed, and they would be in the charge of a warder. Further, the usual prison clothing would be dispensed with. No material other than that which is available on the island would be required for the road construction, where “scoria boulders and the finest gravel is available in any quantity, and sand and shell for binding will be taken from the beach”.[x]

In November, the prisoners – nicknamed ‘the Handy Dozen’ – were on their way. They were, it was reported, “paradoxical as it may appear, a very decent-looking dozen. Giving them a casual glance, one would not dream that they were any but an ordinary working gang about ships, unless it was that they appeared to work with more than usual energy. But a Sherlock Holmes would have had his suspicions aroused by the sign of the broad arrow, stamped on the seat of one man’s trousers — the mark of the convict”. “These men were a selected dozen of the good conduct prisoners at Mount Eden… They had arrived at the wharf at an early hour in the morning, quietly and unostentatiously, in one of the covered-in conveyances provided by His Majesty for the transportation of his compulsory guests. Prisoners have feelings, as well as other humans more fortunate, and the gaol officials took every care that they should not be paraded in the public eye. True, the men were passed on the wharf by crowds from the ferry steamer, but they were hurrying crowds, and if some among them did cast a glance at the workers in dungarees and moleskins (not stamped with the broad arrow), it was doubtful if any guessed at their identity”. It was reported that “there is no fear on the part of the officials that the men will misbehave, but a definite scheme of signalling and communication has been arranged in case of sickness or insubordination, and should anything go wrong, assistance from the mainland will be available in a very short time.”[xi]

In January of 1926, the road “had not yet progressed 200 yds.” [~180 m], but “if a proposal to double the gang now at work is made effective, the road should be completed in well under two years”, reported the Herald. “It will have no grade exceeding one in twenty, so that motor-buses will be able to make the climb at a good pace”. Concerned about visitors to the island, “A notice warns picnic parties that the place is a prison reserve”. The prisoners were housed “in three neat wooden huts, each containing four bunks, with spring mattresses, also a table and two stools. The men work eight and a-half hours a day. They are given a special extra ration of tobacco, making two ounces a week instead of one. Several Devonport people have sent over books to form a small library for their use.”[xii]

Despite the men being selected as good conduct prisoners, two of them, 23-year-old 6ft Charles Wahle – serving two years for forgery and uttering – and 33-year-old Samuel Rattray, 5ft, 8in – undergoing one year’s reformative detention on charges of forgery – “bid a midnight escape, a bright moon assisting them in finding a 12 ft dinghy, which they fitted with a motor from a nearby boat.[xiii],[xiv] They were soon recaptured, however, on nearby Waiheke Island.[xv]

By September 1926, about twenty prisoners are employed on the island: “Great quantities of explosives have been used to break down the solid rock on the island. Most of this work occurred near the landing-stage, where the existing track was widened to form the promenade and from the effect of the explosions the tea kiosk did not escape undamaged”.[xvi] Further, August 1927, it was reported that two men were killed and a number injured in a premature blasting explosion.[xvii]

Hill’s Auckland and Rangitoto Visit

Early in 1928, Arthur Hill visited Auckland, and his whirlwind tour included a trip to Rangitoto Island, Kauri bush in the Waitakere Ranges – which he was impressed by – and Chelsea.[xviii] It was in Auckland that he made his first acquaintance with Kauri in its natural surroundings: “It is a grand thing that these magnificent trees should be so close to your city”, he stated. “There is a kauri 40ft high growing under glass at Kew and some small specimens flourish out of doors in south-west England”.

It was with his visit to Rangitoto, however, where controversy reared its head. Hill certainly didn’t start the fire, as we saw above, but he did re-add petrol to the flames. In the course of his Rangitoto visit Hill displayed a special interest in the kidney ferns growing in places that were not especially well shaded. Overall, he thought the plant life as a whole was most interesting.[xix] Nevertheless, he paid particular attention to the road, which was said to displease him greatly. He remarked that Rangitoto was probably unique in the world because, “as a volcano fairly recently extinct it had been colonised by plants under most interesting conditions”. As such, he believed it should be preserved as a plant sanctuary with as little disturbance as possible. Of particular concern, he was of the opinion that if it were made into a holiday resort, “all kinds of weeds were bound to find their way in”. Dr. Hill was welcomed to the island by Mr. T Walsh, representing the Rangitoto Island Domain Board. Walsh noted that in recognising that the island was unique in its botany, the board was preserving as much of it as they could as a sanctuary for native plants and native birds. Further, he argued that the island was a public domain, and that the best way to preserve it was to make a road from which the public would not wish to deviate. Prominent New Zealand botanist, Dr. Leonard Cockayne, who accompanied Hill through his New Zealand tour, agreed, expressing the opinion that it was best for the board to make a good road and a play area for the public. If this were done, he proposed that the public would be less likely to get among the plants.[xx]

Hill’s opinions continued to be published over the following days. The Sun reported that Dr. Hill declared the road work on the island as “a desecration of nature’s handiwork”, rather than a benefit to the community. “A rest house at the foot, and a good track to the summit would be sufficient”, Hill thought.[xxi]

The New Zealand Hearld, who were the first to report disapproval several years earlier, noted that “when the proposal of a motor traffic road on Rangitoto was first mooted, some opposition was raised regarding the road being unnecessary and of its imperilling the unique character of the island, though this protest aroused little visible support”. They continued that Aucklanders “had permitted the volcanic cones of this neighbourhood to be terribly marred by commercial spoliation, and [had] been largely indifferent to unsightly treatment of the waterfront. The thought of injury [to] Rangitoto has apparently been given no serious heed”. Dr. Hill’s words, they reported, “should stab the city broad awake. What he saw on his visit to the island yesterday moved him to vigorous protest. Rangitoto, in his opinion, is probably unique… The New Zealand botanists sharing the visit to the island endorse his opinion. When so renowned an authority as the Director of Kew Gardens speaks so emphatically, it behoves all citizens to give heed. Motorists will suffer no serious disability if the pleasure of an easy drive to the summit of Rangitoto is denied them… If to open a motor-traffic road on Rangitoto is to destroy the characteristic interest of the island, as Dr. Hill so plainly states, then it certainly ought not to be done… Auckland citizens as a body should be wise enough and vigorous enough to put an end to the menace that has called forth Dr. Hill’s warning.”[xxii]

As with the earlier rounds of debate, Hill’s comments did draw opposition. In an article in Auckland’s Sun Newspaper, one writer stated: “As a scientist in principle and in profession Dr. Hill naturally found Rangitoto Island a realm of curious phenomena, attracting his professional interest. But his suggestions that it, too, should be reserved as a plant sanctuary will not meet with undivided support from the city. There are many arguments against the introduction of motor-cars to Rangitoto. Its mystery and remoteness might at first seem to be destroyed at once by such an invasion. But there are equally strong arguments the other way. Motors and a motor road would permit many elderly or infirm people to reach the summit and revel in the glorious panorama of the gulf, instead of staying below in fear of the laborious walk up the scoria track. It has yet to be shown that a road to the summit would in any way mar the symmetry of Rangitoto’s gentle slope. As for making the place a sanctuary—one island, Motuihi [sic], is already, closed to the public. And one is enough.”[xxiii]

Interestingly, many of the opposing comments seemed to go beyond what Hill had even suggested – inferring that he had called for Rangitoto to be free of humans altogether. Referencing Hill, Sir. E. Aldridge, chairman of the Rangitoto Island Domain Board, stated: “It is hardly a fair proposition for a man to spend an hour at Rangitoto and then advocate shutting it off from the public forever”. Aldridge had been unable to visit the island with Hill and the official accompanying party, but the board was represented by Mr. T. Walsh. Walsh reaffirmed that Dr. Hill was on the island barely an hour, and the whole of that time he was occupied in viewing and discussing botanical subjects. He went on to declare that “Dr. Hill was quite ignorant of local conditions. It is now too late to make Rangitoto a sanctuary, because it has been open for the past 80 years”. Walsh further added the island had always been open to boatmen and the Harbour Board worked a large quarry there. In addition, there was now a settlement and a school on the island, while twice within his memory the island had been swept by fire. Even if it were desirable to make Rangitoto a sanctuary, he was of opinion it would not be possible: “They would have to provide a large guard to prevent people landing there”. Another, unnamed, member of the board was equally as scathing, stating, “These were chance remarks made by a man who had not enough time to know the facts”. Yet another said he was quite sure that by building a road on the island they were opening it up for the great benefit for the people, not only of Auckland, but also of the whole of New Zealand, and overseas tourists. A Mr. J Brown declared that the area to be taken up by the road would only be “a drop in the ocean” compared with the area of the island. Other printed dissenting comments included, “We do not want to take notice of criticism such as this”, and, “The proportion of people interested in botany is very small”.[xxiv]

Following these criticisms, others came out in support of Hill. The Curator of the Auckland Museum, Mr. Gilbert Archey, was “in hearty accord” with the opinion expressed by Hill that Rangitoto should be kept as a reserve on account of the extreme importance of its flora: “He knows that once these plants are destroyed they can never be replaced”. “He does not look upon such an area from a social, or sports, point of view. He regards it purely in the light of its value to the world of learning. Personally, I think Dr. Hill is quite right”, he added.”[xxv]

In a letter titled Rangitoto Spoilation, JA James of Devonport wrote that Hill’s condemnation of the roading of Rangitoto “is only what may be expected from any man having… a regard of Nature’s marvellous handiwork”. He also acknowledged the Herald’s comments on the little support given to the opposition raised at the time the motor road was first mooted: “As one who then protested, I was amazed at the lack of interest in protecting this unique natural heritage from such vandalism. There certainly is no need for such a road, and the bare thought of motors on Rangitoto should be utterly repugnant to anyone in his right senses. I trust, now that this spoliation has been again brought under public notice, action will be immediately taken to stop the work. The portion of road already made will remain a ghastly monument to the crass ignorance of its originators. All we want on Rangitoto is a walking track to the summit. No vehicle of any description should be allowed. Wake up Auckland and save Rangitoto. Given a motor road, and the consequent vehicular ferry, and you have committed irreparable vandalism.[xxvi]

A few days later, Hill departed the country. In some parting statements, he defensively responded to the press reports. He noted that when he had “mildly suggested” that in view of the unique character of the island and its flora such a road was unwarranted he was “hauled over the coals” by the local Press, and told he should not have the temerity to criticise after an hour’s visit to the island: “A botanist could see, after a ten minutes visit, that such a road would inevitably mean the introduction to the island of a miscellaneous collection of weeds, and then gone would be the uniqueness of the island”. He maintained his opinion on this point. He reiterated that Rangitoto should be left to the pedestrian and to nature.[xxvii] “I still stick to my guns on this point: there are many other hills around Auckland much more suitable for a motor road: Rangitoto should be left to the pedestrian and Nature”.[xxviii]

The Road Post Hill’s Visit

Ultimately, the road construction was completed despite the furore. Some modifications needed to be made, however. In May 1928, Mr. Aldridge announced that it would not be possible to construct the motor road to the summit of the cone owing to the nature of the soil: “It will go, however, as far as the saddle.”[xxix] Aldridge added, “The ground is very soft, and the grade is so great that with wet weather or heavy traffic the road would slip badly. However, we can take the road up to the saddle without much difficulty, and there will not be a great climb from there.”[xxx]

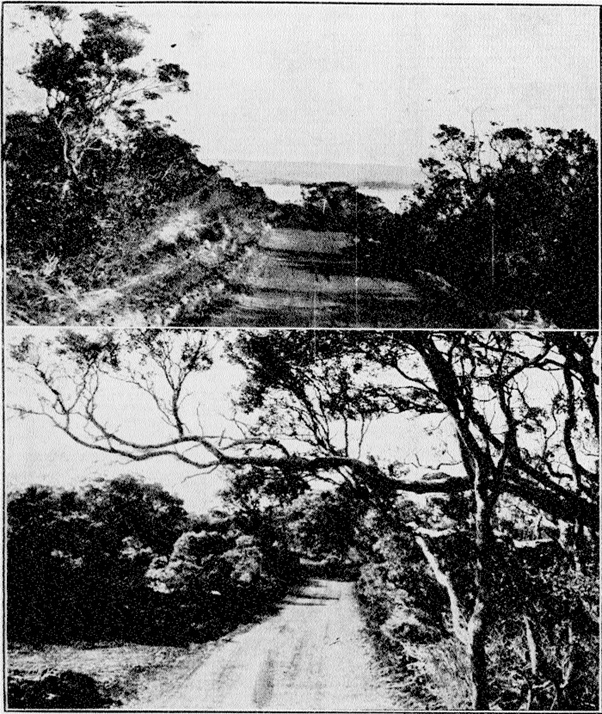

In August 1928, it was optimistically stated that the completion of the road to the summit was expected to take another six months.[xxxi] Fast forward two years, and it was announced on 10 July 1930 that the new scenic route was to be opened the following Saturday. It was also noted that the road that should last, in the opinion of the authorities, “for all time”.[xxxii] This opening estimate, too, was still getting ahead of itself, as 12 July was actually the day the road was inspected by members of the Domain Board; the date of the opening of the road had not yet been decided.[xxxiii] The inspection party left the city by the ferry steamer Condor, and was conveyed over the new road in a fleet of nine “baby” cars. Islington Bay was reached “after a few minutes run over a fine scoria-surfaced carriageway, the distance from the wharf being about three miles”. The party then travelled over the crest of the mountain. Excellent work was said to have been done and it was hoped that it would be ready for public use by the end of the year.[xxxiv] By October 1930, arrangements had been made to start a bus service on the island, and the first vehicle to cater for visitors was shipped there by one of the vehicular ferries.[xxxv] The bus service started soon thereafter. Today, a tractor powered ‘road train’, the Rangitoto Island Volcanic Explorer, still uses the road.

Acknowledgements

Cover image by Bruce Hayward, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

References

[i] Rangitoto Island. New Zealand Herald, 19 February 1925, P7

[ii] Rangitoto Island. New Zealand Herald, 19 February 1925, P7

[iii] Road on Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 3 April 1925, P10

[iv] Rangitoto Island. Auckland Star, 27 July 1925, P9

[v] Roading Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 28 July 1925, P8

[vi] Motors on Rangitoto. Auckland Star, 28 July 1925, P6

[vii] Motoring on Rangitoto. Auckland Star, 30 July 1925, P10

[viii] Auckland Star, 29 July 1925, P9

[ix] The Rangitoto Road. New Zealand Herald, 1 August 1925, P12

[x] Developing Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 13 August 1925, P11

[xi] Rangitoto. Auckland Star, 26 November 1925, P10

[xii] Developing Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 7 January 1926, P10

[xiii] At Liberty. Auckland Star, 2 February 1926, P5

[xiv] Prisoners Escape. New Zealand Herald, 3 February 1926, P12

[xv] Short-Lived Freedom. Auckland Star, 6 February 1926, P10

[xvi] Road on Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 27 September 1926, P11

[xvii] Two Prisoners Killed In Quarry Explosion. Star (Christchurch), 19 August 1927, P5

[xviii] Auckland Star, 6 February 1928, P5

[xix] Unique in the World. Auckland Star, 7 February 1928, P8

[xx] Unique in the World. Auckland Star, 7 February 1928, P8

[xxi] The Voice of Nature. Sun (Auckland), 7 February 1928, P8

[xxii] Preserving Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 7 February 1928, P8

[xxiii] Sun (Auckland), 7 February 1928, P8

[xxiv] Rangitoto’s Destiny. New Zealand Herald, 9 February 1928, P11

[xxv] Saving Plant Life of Rangitoto Island, Sun (Auckland), 13 February 1928, PAGE 1

[xxvi] Rangitoto Spoilation. New Zealand Herald, 10 February 1928, P14

[xxvii] What are “Reserved”? Auckland Star, 14 February 1928, P9

[xxviii] Evening Post, 14 February 1928, P10

[xxix] Table Talk. Auckland Star, 24 May 1928, P1

[xxx] Road on Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 24 MAY 1928, P10

[xxxi] Roads on Rangitoto. New Zealand Herald, 6 August 1928, P11

[xxxii] News of the Day. Auckland Star, 10 July 1930, P6

[xxxiii] News of the Day. Auckland Star, 11 July 1930, P6

[xxxiv] New Scenic Drive. New Zealand Herald, 14 July 1930, P6

[xxxv] News of the Day. Auckland Star, 24 October 1930, P6