Ian Duggan

A number of newspaper reports were published in the early 20th Century on the figureheads of ships featuring as items of statuary in New Zealand gardens. In previous blogs we examined the stories of the figureheads of the Hydrabad and HMS Wolverine. But there have been plenty of reports of others that have adorned our gardens besides these. Though not exhaustive, in this final contribution I examine the interesting stories of several more of these, including the figureheads of the America and the Helen Denny.

AMERICA

One of the most interesting remaining stories of ship figureheads appearing in New Zealand gardens is that of one that had lost its provenance. In March 1930, it was reported that an “exceptionally fine figurehead, true to nautical regulations in being one and a-half times life size, has lost her identity. For many years she reposed in the garden of Mr. J. J. Craig’s house, in Mountain Road [Epsom], but after 23-4 years no one remembers where she came from”.[i]

Soon after, this figure – like that of the Wolverine in our previous blog – made its way into the collection of ships’ figureheads at the naval headquarters in Devonport, Auckland. Despite the origin being unknown, it was noted to be “in an excellent state of preservation”. The figure was “that of a girl dressed in Grecian costume. The figure is a particularly fine one, and represents a very high degree of perfection in the art of wood-carving. The features are well-proportioned and the flowing garments have a most realistic appearance.”[ii]

It took some time to be confident of its origin, but it was “solved after four months’ investigation by Mr. T. Walsh, of Devonport, who undertook the task at the request of Commander Nelson Clover, [the] officer commanding the naval base at Devonport”.

Of the Devonport naval collection, the figurehead was described as the “largest and most ornately carved”. At first it was assumed to have come from the Constance Craig. “An inspection of the figurehead at the dock”, however, led to the conclusion that it did not come from this vessel: “Practically all the “shell backs” [a term used for an old or experienced sailor, especially one who has crossed the equator] to be found about Auckland waterfront, were consulted about the possible origin of this old piece of ship ornamentation. The Joseph Craig, the Hazel Craig, the Quathlamba, and the Royal Tar were mentioned as being likely ships, but in each case investigation proved that the figure-head did not come from any of the vessels mentioned. The possibility that the late Mr. J. J. Craig had bought the figurehead in Fiji or elsewhere was then examined. After 60 inquiries had been made a chance meeting with a carter formerly employed by J. J. Craig, Ltd., elicited that for many years the figurehead had reposed in a shed on the old Railway Wharf. The following up of this line of inquiry led eventually to establishing that the figurehead belonged to the ship America, which put into Auckland in distress in 1903 and was condemned here”.

Research uncovered at the time found that the America had started life in 1868 under the name ‘Mornington’. “In July, 1903, she sailed from Newcastle [Australia] with 2,400 tons of coal, but was two days out when a leak developed in the stern”… “The ship put into Auckland, and the captain made a great fight to save his ship. She was condemned on September 3, 1903, and cargo and ship were sold. Some years later the ship was dismantled and anchored in “Rotten Row.” When the American fleet visited the Waitemata, in 1908, the America left her moorings and fetched up alongside one of the worships. The weather was exceedingly rough, and every effort to shift the hulk failed”… “the old hulk was taken to the “bay of wrecks” at Pine Island, where holiday-makers subsequently set her afire”.[iii]

HELEN DENNY

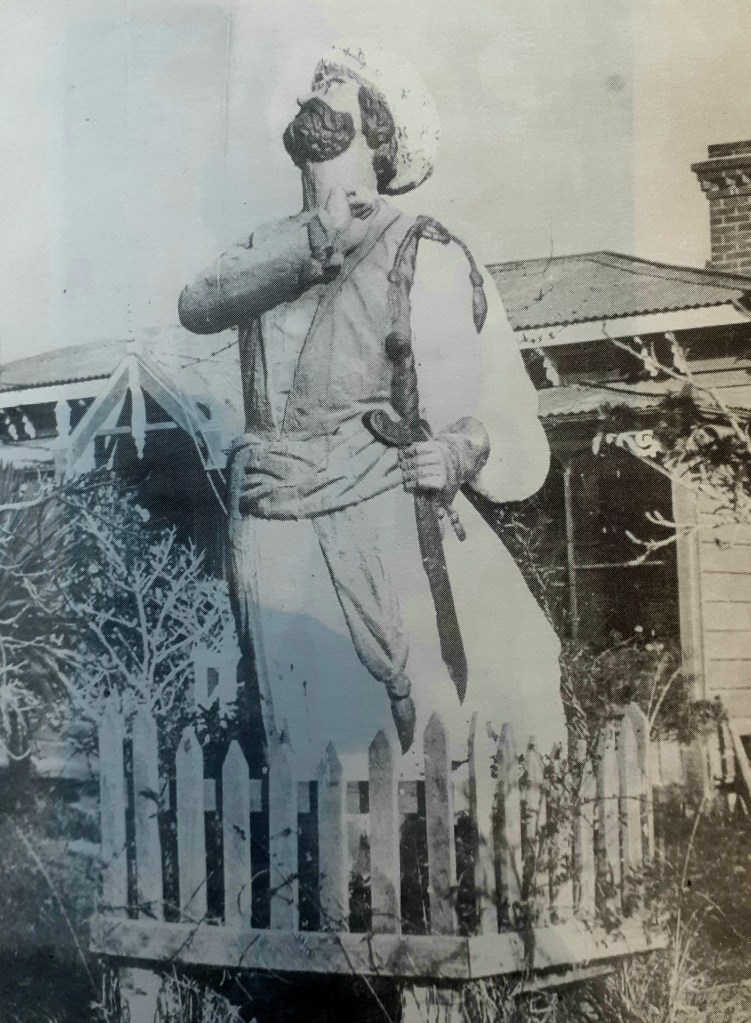

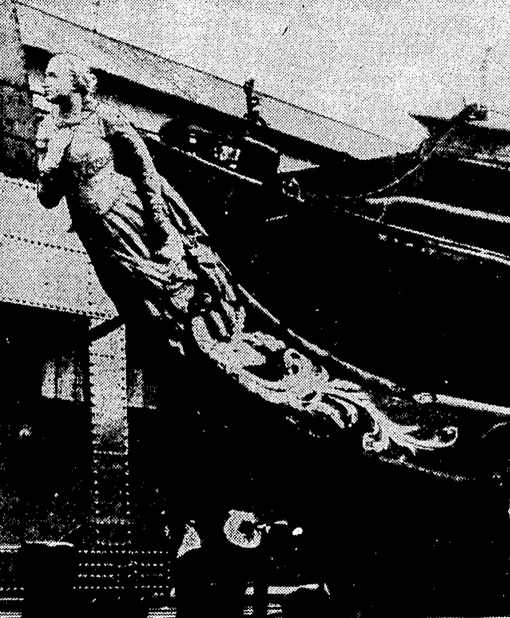

Many column-inches, commonly with some of the most spectacular images, were dedicated to the figurehead of the Helen Denny. In 1935, “after having been lost track of for a number of years”, The Evening Post reported that “the figurehead of the intercolonial barque Helen Denny has turned up again. The figurehead, which is in a remarkable state of preservation, is the property of a Roseneath [Wellington] resident, and is to be mounted in a garden overlooking the harbour where the old vessel spent many years as a hulk”.

“The form of the figurehead is such as was familiar in bygone days, and is that of a lady attired in a white dress of the mid-Victorian, period, trimmed with green and gold. Clasped in her right hand on her breast is a red rose. She has black hair surmounted by a coronet, and gold bangles encircle her arms”.

The Helen Denny was described as “an iron ship of 695 tons, with a length of 187.5 ft”, and was said to have “took the water in the Clyde in 1866”. “The name Helen Denny was bestowed upon her as a compliment to the wife of the then manager of Denny and Company, the famous Dumbarton shipbuilders… The figurehead is intended as a likeness of that lady, and although its merit cannot readily be judged by comparison, it appears to be a remarkably fine piece of work”. [iv]

“For 10 years she traded out of Glasgow to Rangoon [now Yangon, Myanmar] and those exotic eastern ports… Then the Shaw, Savill Company bought her and brought her into New Zealand waters”.[v] For many years, the Helen Denny was well known as a trader and cadet ship on the New Zealand coast.[vi]

Evening Post, 10 October 1936, P24

The barque was dismantled in 1912 for service as a hulk, after which the figurehead was said to have “certainly had a chequered history”.

The Evening Post in 1935 noted that: “Many years ago it was picked up off the beach by a shipping clerk, now retired, who had it in his garden at Roseneath for some time before passing it on to its present owners. What happened to it prior to this and how it came to be on the beach are not known. There is a well authenticated story to the effect that when Colonel Denny visited New Zealand many years ago, he asked for the figurehead. The company which then had the vessel promised to let him have it when she went out of commission, but this was never done”.[vii]

The figurehead sat in that Roseneath garden for several years. In 1938, it was reported, rather poetically, that “Standing among the flowers of a Roseneath garden, the carved wooden figure of a graceful woman watches with unblinking eyes the steamers loading and discharging merchandise, the fussy tugs, the harbour ferries, yachts, coal-hulks, all the colourful shipping of the port of Wellington. She is watching doubtless, for the coming of the tall and stately sailing vessel whose figurehead once she was—but the old barque Helen Denny, last and loveliest of the colonial clippers, is ending her days as a battered bulk in Lyttelton.”[viii]

Evening Post, 30 October 1937, P 24

Other Figureheads in Gardens

Finally, I provide here short notes on three other vessels, whose figureheads were noted in New Zealand suburban gardens. Again, however, this coverage is by no means exhaustive, with snippets of others also appearing in various newspapers in the early 20th Century.

NORTHUMBERLAND

The figurehead of the Northumberland, featuring “a warrior with a sword”, rested “in the garden of Mr Frank Armstrong, at Akitio”, in the Manawatū-Whanganui region.[ix] The Northumberland was wrecked on the Petane Beach (Napier), on May 13th, 1887”. A 1910 report noted that “After the officers and crew of the Northumberland were saved the vessel broke up and the figurehead was the only thing saved”.[x] A story from the 1920s, however, suggested that more was salvaged. The Hawera Star informed its readers that in the cargo of the ship there “was a quantity of rum”… “and some of it was among the first of the flotsam to come ashore. The crowd immediately broached it and got very tipsy, giving the police a lot of trouble”. This report noted that the “figurehead of the Northumberland was secured by a Westshore fisherman, and was for years a prominent object in his garden”.[xi]

AGNES JESSIE

The “figurehead of the barquentine Agnes Jessie, which was wrecked with the loss of five lives” on Mahia Peninsula while on route between Lyttelton and Auckland[xii] in 1877, was “discovered in the garden of Mrs. K. Northe, of Havelock Street, Napier” in the 1930s. The Auckland Star reported that the “figurehead is in a splendid state of preservation, and represents a young woman in the dress of the early Victorian period. It has been in the possession of Mrs. Northe’s family for nearly 40 years, having been washed ashore nearly two months after the wreck happened”.[xiii]

ROBINA DUNLOP

The Robina Dunlop was wrecked in the mouth of the Turakina River, while in transit between Wellington and Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia) in 1877.[xiv] In 1924, the Manawatu Times reported on a Mr John Grant of Turakina, who was “was an interested visitor at Saturday’s All Black match. He is 73 years of age and from his upright lissome figure, looks as though he could still play the game with the best of them”. Although it is unclear why this was part of the story, it continued: “Nearly sixty years ago he carried the carved figurehead of the wrecked vessel “The Robina Dunlop” on horseback from the beach, to his father’s home, where it still stands in the garden, a beautifully carved-life slzed representation of the lady after whom the vessel was named”.[xv] This figurehead, also, was later presented to the Devenport Naval base collection in 1936 by Mrs. M. Grant.[xvi]

Read Part I here: The Hydrabad

Read Part II here: The Wolverine

References

[i] Sun (Auckland), 22 March 1930, P 17

[ii] Ship’s Figureheads. Wanganui Chronicle, 24 March 1930, P 2

[iii] Curious Figurehead. Sun (Auckland), 5 June 1930, P 10

[iv] An Old Figurehead. Evening Post, 25 September 1935, P 13

[v] Figurehead of the Helen Denny. Dominion, 23 August 1938, P 3

[vi] Evening Post, 25 September 1935, P 9

[vii] An Old Figurehead. Evening Post, 25 September 1935, P 13

[viii] Figurehead of the Helen Denny. Dominion, 23 August 1938, P 3

[ix] John Knox’s Figurehead had a Movable Arm .Star (Christchurch), 7 June 1930, P 21 (Supplement)

[x] New Zealand Graphic, 23 November 1910, P 18

[xi] Local and General. Hawera Star, 7 February 1927, P 4

[xii] Wreck of the Agnes Jessie. West Coast Times, 29 June 1882, P 2

[xiii] News of the Day. Auckland Star, 24 March 1936, P 6

[xiv] Total Wreck of the Barque Robina Dunlop. New Zealand Times, 15 August 1877, P 2

[xv] Personal Paragraphs. Manawatu Times, 29 July 1924, P 4

[xvi] Three More. Auckland Star, 26 March 1936, P 10