Annette Giesecke, Te Herenga Waka | Victoria University of Wellington

I tried to grow yarrow in my Pennsylvania woodland garden to no avail, but on my New Zealand plot, surrounded by orchards and pasturelands, it grows rampant, undeterred by drought or clay soil. A member of the Asteraceae family and native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, this handsome perennial plant reaches a height of up to 1 metre (3.5 feet); has fernlike, finely dissected leaves; and its flat or slightly convex flower heads, blooming from spring well into autumn, consist of clusters of small flowers. In the wild, its flowers range in colour from white to pink, but there are red, orange, hot pink, lavender, and yellow cultivated varieties available in garden centres.

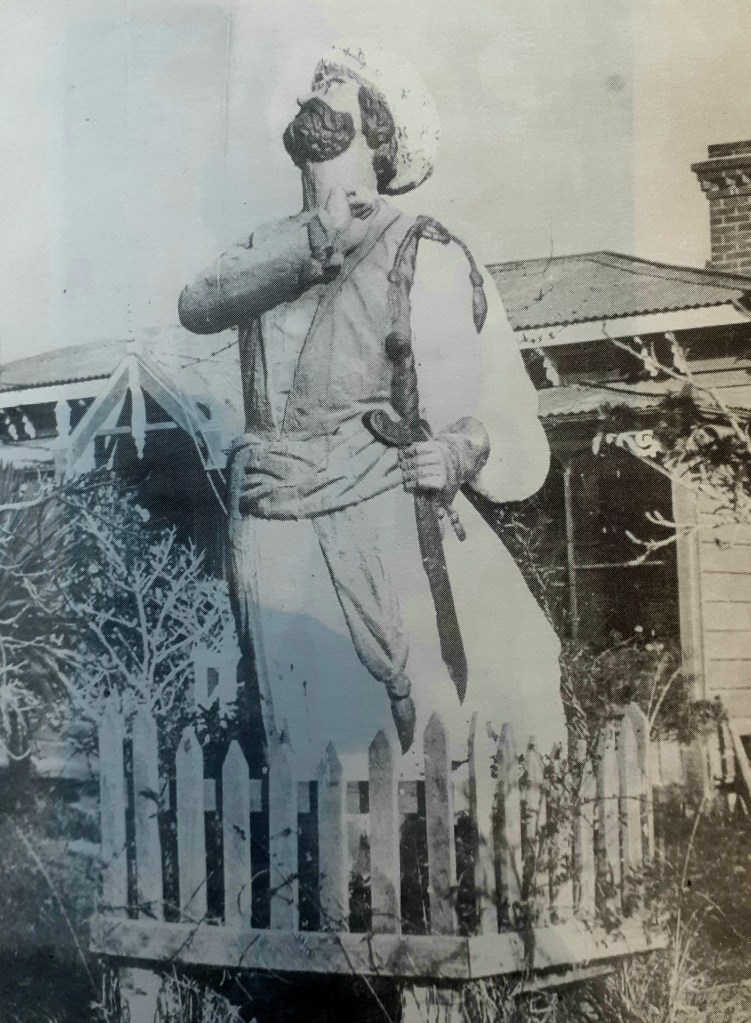

Known also in common parlance as ‘arrowroot’, ‘death flower’, ‘eerie’, ‘hundred-leaved grass’, ‘old man’s mustard’, ‘sanguinary’, ‘seven-year’s love’, ‘snake’s grass’, and ‘soldier’ – yarrow is interesting on so many levels. When established, it is hardy even in adverse conditions, and it is of significant value to wildlife. Its nectar-rich flowers attract butterflies, bees, and other insects, while its leaves, toxic to some animals (including dogs, as I have witnessed), are grazed by others and gathered by nesting birds. The whole plant has a distinctive, sharp odour, that can be described as a mixture of chamomile and pine, or chrysanthemum-like. To the taste, its roots are bitter. Yarrow has been used by humans for millennia as a medicinal plant, useful in treating a wide range of ailments ranging from headaches and indigestion to infections. It effectively staunches bleeding and repels mosquitoes as well. Yarrow also has applications as a fabric dye, yielding a range of yellow tints. And then there is its mysterious botanical name, Achillea millefolium, which translates as ‘Achilles’ thousand-leaved plant’. ‘Thousand-leaved’ is, of course, a reference to yarrow’s dissected leaves, but why is this the plant of Achilles, that ancient Greek hero famed for his exploits in the Trojan War?

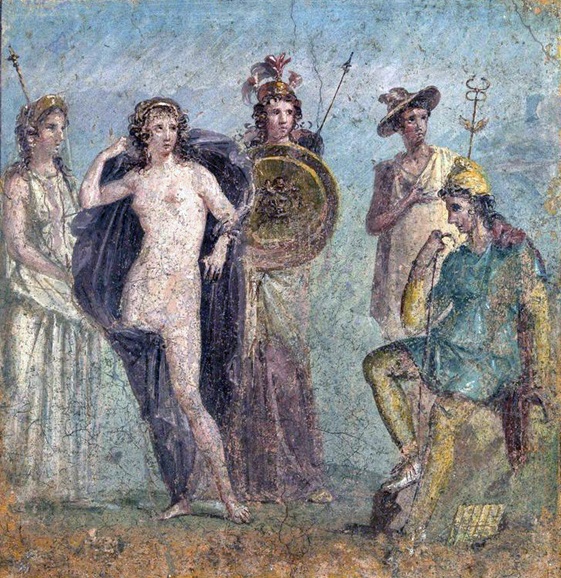

In addition to being an extraordinarily effective warrior, Achilles had a range of other skills and talents, all in keeping with his unusual parentage and upbringing. He was the son of the sea goddess Thetis and Peleus, a mortal man. A prophecy had revealed that Thetis was destined to bear a son who would overpower his father, an event that would threaten the established divine hierarchy. For this reason, Zeus, king of the Olympian gods, offered Thetis in marriage to Peleus, a king of the northern Greek district of Phthia, for whom this was a reward. By some accounts, Thetis did not accept this arrangement willingly, causing Peleus to wrestle with her as she changed her shape to fire, water, and then a wild beast to elude his grasp (Apollodorus, Bibliotheca. 13.3). Peleus prevailed, and all the gods were invited to the couple’s wedding… all but one. Only Eris, goddess of strife was excluded. Her presence on this festive occasion, it was thought, would only bring misfortune. Misfortune befell the festive gathering nonetheless, as an angry Eris appeared bearing what would prove to be a fateful wedding gift: a golden apple labeled ‘for the fairest’. Loveliest of the goddesses were Hera (queen of the gods), Athena (goddess of wisdom and defensive war), and Aphrodite (goddess of love and desire), and all three, equally beautiful, laid claim to this golden prize. As no god dared to make this choice, it was agreed to leave the decision to Paris Alexander, the prince of Troy, whose reputation as a lover was well known. Not leaving the outcome of this contest to chance, each goddess offered Paris a bribe. Hera promised that she would make him king of all men, while Athena offered him success in war. Aphrodite, however, knew him best and offered him Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world. It was she who was awarded the golden apple.

In the course of time, Paris traveled to Greece and, while being hospitably entertained in Sparta, made off with Helen, that kingdom’s queen. This was an affront that King Menelaos, Helen’s husband, could not bear, and with his brother Agamemnon, king of Mycenae in the lead, assembled the bravest and strongest men of Greece. A fleet of one thousand ships then sailed to Troy, their purpose being to retrieve Helen, a goal not easily achieved as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey reveal.

Between Paris’ fateful judgment and his theft of Menelaos’ queen, some fifteen years had passed. Soon after the wedding of Peleus to Thetis, Achilles was born to them, and although half-divine by birth, he was destined to die an early death, as a prophecy foretold. His distraught mother attempted to make her infant immortal, holding him by the ankles and dipping him in the magical waters of the dreaded river Styx. This left him invulnerable, except on his ankles where his mother had held him fast.

While a young child, Achilles, like several other Greek heroes, was sent to live with and be educated by Chiron, a very special centaur. Others were Jason, who went to fetch the famed Golden Fleece; Hercules, renowned for his 12 Labours; and Asklepios, the god Apollo’s son who would become a god of healing. From Chiron, Achilles learned how to hunt, how to play the lyre, and, of particular relevance to yarrow, how to use herbs in healing.

When grown, Achilles would join the Greek forces who fought for the return of Helen, in the course of battle displaying extraordinary cruelty—especially towards Hektor, Troy’s brave and kind defender, a wholly decent, honourable man—but also extraordinary compassion towards his wounded comrades. In Homer’s Iliad, one particular wounded warrior, Eurypylos by name, was not attended to by Achilles himself but by Achilles’ closest friend, whom he, in turn, had instructed in the art of healing. Eurypylos had pleaded for Patroklos’ help, saying:

“Please, I beg of you, lead me to my dark ship, and cut this arrow from my thigh. Warm water will wash away the blackened blood, and then sprinkle good, soothing medicines (ēpia pharmaka esthla) upon it, just as people say Achilles taught you”. (Iliad XI. 828-31)

What, exactly, this good, soothing medicine consisted of is not stated here, but the following lines offer a significant clue:

“Patroklos lay him down, and cut the piercing arrow from his thigh, washing away the dark blood with warm water. And he placed a bitter root upon the wound, first rubbing it with his hands, a root that kills pain (rhizdan pikrēn) and that put an end to all his suffering. The wound was dry, the bleeding stopped”. (Iliad XI.844-48)

Homer did not name this bitter root, but yarrow’s root is bitter, and the plant has analgesic (painkilling) and hemostatic (blood-stopping) properties as well.

The Iliad is conventionally dated to about 750 BCE, and it would be more than 700 years later that Roman encyclopedist Pliny the Elder, author of a multi-volume Natural History (first century CE), provided the next clue: “Achilles, too, the pupil of Chiron, discovered a plant which heals wounds, and which, as being his discovery, is known as the ‘achilleos’ [plant of Achilles].” Yet Pliny proceeded then to identify this plant with one very different from yarrow, writing:

“By some persons this plant is called ‘panaces heracleon’, by others, ‘sideritis’, and by the people of our country, ‘millefolium’: the stalk of it, they say, is a cubit in length, branchy, and covered from the bottom with leaves somewhat smaller than those of fennel. Other authorities, however, while admitting that this last plant is good for wounds, affirm that the genuine achilleos has a bluish stem a foot in length, destitute of branches, and elegantly clothed all over with isolated leaves of a round form. Others again, maintain that it has a squared stem, that the heads of it are small and like those of horehound, and that the leaves are similar to those of the quercus—they say too, that this last has the property of uniting the sinews when cut asunder. Another statement is that the sideritis is a plant that grows on garden walls, and that it emits, when bruised, a fetid smell; that there is also another plant, very similar to it, but with a whiter and more unctuous leaf, a more delicate stem, and mostly found growing in vineyards”. (Natural History 25.19, adapted from John Bowersock trans. 1855. London: Taylor and Francis)

Pliny offered several plants as candidates for Achilles’ plant. One is sideritis (‘mountain tea’), a group of plants in the mint family that don’t remotely resemble yarrow physically but that do have medicinal properties. Another is ‘panaces heracleon’ (‘Hercules’ cure-all’, Opopanax chironium), a yellow-flowering herb that grows 1-3 metres in height but that likewise has medicinal applications. Did Pliny confuse these two with the plant that, much later, with the advent of standardized scientific botanic nomenclature, would be called Achillea millefolium? Or, were all three simply known as ‘Achilles’ plants’ in antiquity? All we can say is that it was Achilles’ reputation as a healer of battle wounds that inspired the choice of yarrow’s scientific name by Carl Linnaeus in the 18th century.

*All translations of ancient texts are by the author unless stated.

Modern Sources:

Christopher Brickell and Judith D. Zuk (eds.). 1996. The American Horticultural Society, A to Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. New York: DK publishing.

David J. Mabberley. 2014. Mabberley’s Plant-book: A Portable Dictionary of Plants, their Classification and Uses 4th Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Annette Giesecke. 2020. Classical Mythology A to Z: An Encyclopedia of Gods & Goddesses, Heroes & Heroines, Nymphs, Spirits, Monsters, and Places. New York: Black Dog and Leventhal.

Herb Federation of New Zealand: https://herbs.org.nz/herbs/yarrow-international-herb-of-the-year-2024/